The approaches to large temples and shrines are fringed with a number of teahouses and souvenir shops.

It was in the Muromachi period when vendors started to gather in front of temples and shrines. In those days, few merchants had shop buildings.

What, then, were teahouses in the Muromachi period like?

In those days, tea vendors were called “Ippuku Issen (lit. one cup of tea for one sen (a unit of currency))”. They brought tea utensils to the temple town, and sold tea to visitors to the temples and shrines. Ippuku Issen were also depicted in pictures.

From the late Muromachi period to the Edo period, a number of folding screen pictures were drawn, called “Rakuchu Rakugai-zu Byobu (“洛中洛外図屏風” folding screens with pictures of inside and outside Kyoto)”.

These pictures depicted scenes in the central Kyoto, and people of diverse occupations who lived there. The “Ippuku Issen (一服一銭)” tea vendors were among them. The pictures show that tea vendors spread mats in front of temples and shrines, put up a fireplace on them, and brewed tea. Other vendors carried kettles and water buckets with a shoulder pole to peddle tea.

The town in front of the Minamidaimon gate of the Toji temple was crowded with many visitors, and tea vendors also gathered to sell tea to them. The Toji Hyakugo Archives include several documents related to such trading in temple towns. These documents show what merchants were like in those days, and how Toji reacted to them.

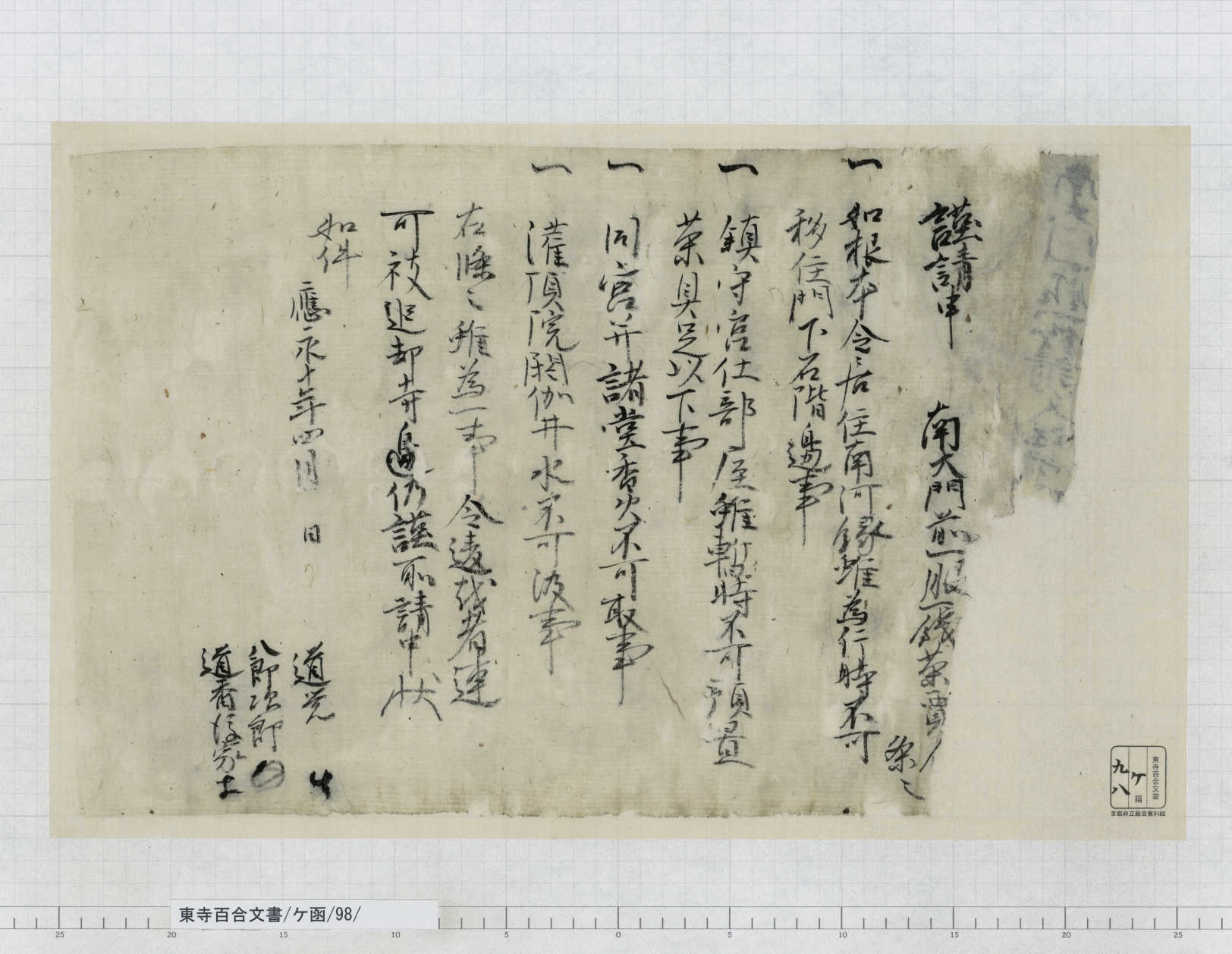

In April 1403, Toji had tea vendors submit the following Ukebumi (請文) (written oath) (Item 98 of Box-KE (Katakana)).

With this oath, Toji required tea vendors:

○ To live where they have been living, and not to live on stone steps in front of the temple;

○ Not to deposit tea utensils in the room of Miyaji (宮仕) (lower shrine priests) for the Chinju-Hachimangu shrine (鎮守八幡宮) in Toji;

○ Not to take a pilot fire from incense sticks in the temple halls;

○ Not to draw water from the Akai (wells for water to be offered to the deity) in the temple halls;

among other requirements.

It is suggested that Toji went so far as to have vendors submit written oaths, because the listed acts did not cease, and Toji was worried about the management of fires and other risks. At the end of this document, it is stated that vendors who violate these rules would be expelled from the Toji area.

Nevertheless, the worries of Toji came true exactly one year after these written oaths.

A fire broke out, originated by a hibachi (火鉢) (charcoal burner) that a tea vendor deposited with a Kotsujiki (乞食) (mendicant monk) beside Minamidaimon(南大門).

Even though the fire did not spread, but was successfully put out, Toji held a Hyojo (評定) (meeting) on the same day, and decided to expel tea vendors from the Toji area.

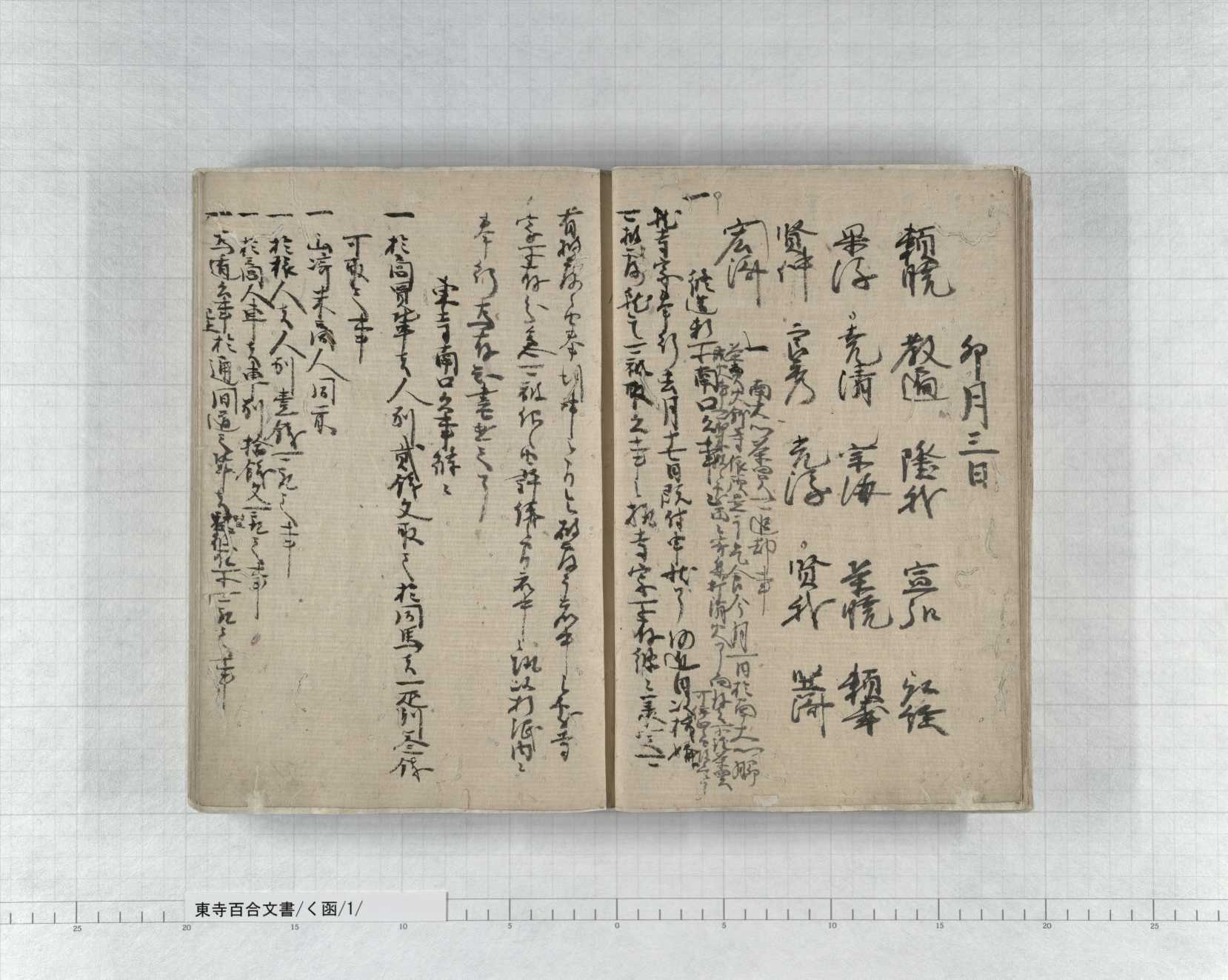

The Hikitsuke (引付) (minutes of the meeting) (Item 1 of Box-KU (Hiragana)) records that decision process.

The photo above shows the date, the names of Guso (供僧) (monks who serve the principal object of worship at a temple), and the agenda items. Immediately following the names of Guso, a statement was added in smaller letters, “一 南大門茶買(売)可追却事 (1 Tea vendors should be expelled from Minamidaimon).” This indicates that the sudden incident was urgently included into the agenda for the day’s Hyojo.

“追却 (‘tsuikyaku’)” means to expel. Would the tea vendors really be expelled at this order? What would be their fate? Wait for the next story.