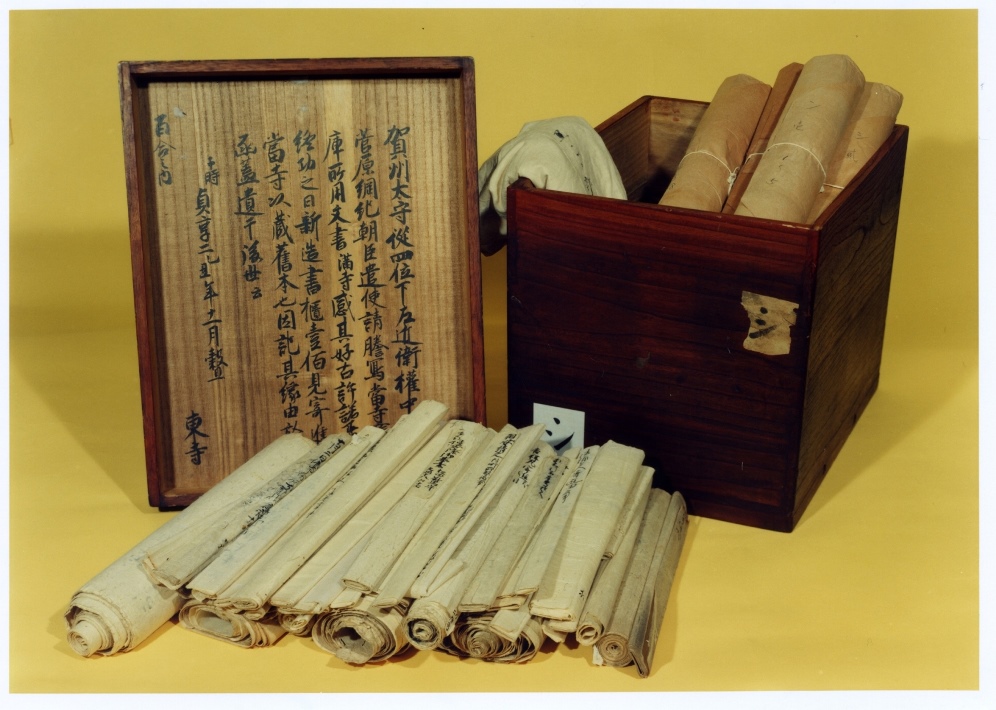

Today’s story behind the Hyakugo Archives is not about the content of the documents, but about the Kiribako (boxes made of paulownia wood) that contain them.

This topic was inspired by a question that Ms. K, 100 years of age, asked me. Isn’t he a wonderful combination for a story behind the Hyakugo (lit. 100 boxes) Archives?

Ms. K was born on February 24, 1914, and celebrated her 100th birthday 2014 year.

When I visited Ms. K in June 2014, the Toji Hyakugo Archives (東寺百合文書) came up in conversation. Our common acquaintance, Ms. F, is a fan of the Toji Hyakugo Archives. When Ms. F was mentioned in our talk, I referred to the Toji Hyakugo Archives. Ms. K immediately responded to me, saying, “the Hyakugo Archives, they are going to be on the UNESCO’s Memory of the World list, right?” It was only two days before that when the Toji Hyakugo Archives were officially selected for recommendation to the UNESCO’s Memory of the World list, so I was surprised at the speedy information collection by Ms. K. In fact, it turned out that he did not know of the official selection, but had known that the Hyakugo Archives were included in the list of candidates for recommendation. Anyway, it was amazing that Ms. K promptly recalled the term “UNESCO” in a conversation at the age of 100.

Then Ms. K asked a keen question, “Are the boxes of the Hyakugo Archives lacquered?” I was taken aback by this unexpected question, and barely answered “Those boxes are made of paulownia wood (桐箱), and are not lacquered.” On second thought, I remembered that some boxes made of paulownia wood were actually lacquered, but at that point, that was the best answer I could think of, with only gorgeously lacquered letterboxes in my mind. Ms. K seemed surprised at my answer, saying, “Oh, I had assumed that they were lacquered.” His reaction drew my attention. In fact, the boxes of the Hyakugo Archives were brown-colored, and it was unlikely that the wooden plates turned into such colors merely due to changes over time. Therefore, some kind of coating seemed probable through careful examination.

I researched about lacquer work, and learned that there was a technique called “Fuki Urushi (拭き漆)”, where lacquer craftsmen repeat the process of applying transparent raw lacquer to wooden plates and then wiping it off with a cloth, thereby finishing lacquer work with the beautiful appearance of grain. So there was a possibility that the boxes of the Hyakugo Archives were lacquered. Then I consulted Ms. S, a friend of mine and curator specialized in lacquer work and other craft products. Through comprehensive examination on the color and luster of the box, the way of application on the back of the box, etc., Ms. S advised me that the boxes seemed to be made of lacquered wood that was pretreated with persimmon juice. He told me that persimmon juice had the effects to keep off insects, mold and moisture, and that this technique was inexpensive, because the required amount of lacquer became smaller compared to a method of directly applying lacquer. Pretreatment with persimmon juice also enhances durability, he said. Boxes made of paulownia wood are characteristic in their lightness, excellent humidity control, and resistance to cracks and warps. They are also resistant to fires, because of their extremely low heat conductivity. In this way, the optimal letterboxes become available by applying coatings as described above to boxes made of paulownia wood.

Therefore, the most adequate answer to Ms. K’s question would be “the boxes of the Hyakugo Archives are made of paulownia wood, pretreated with persimmon juice and lacquered”.

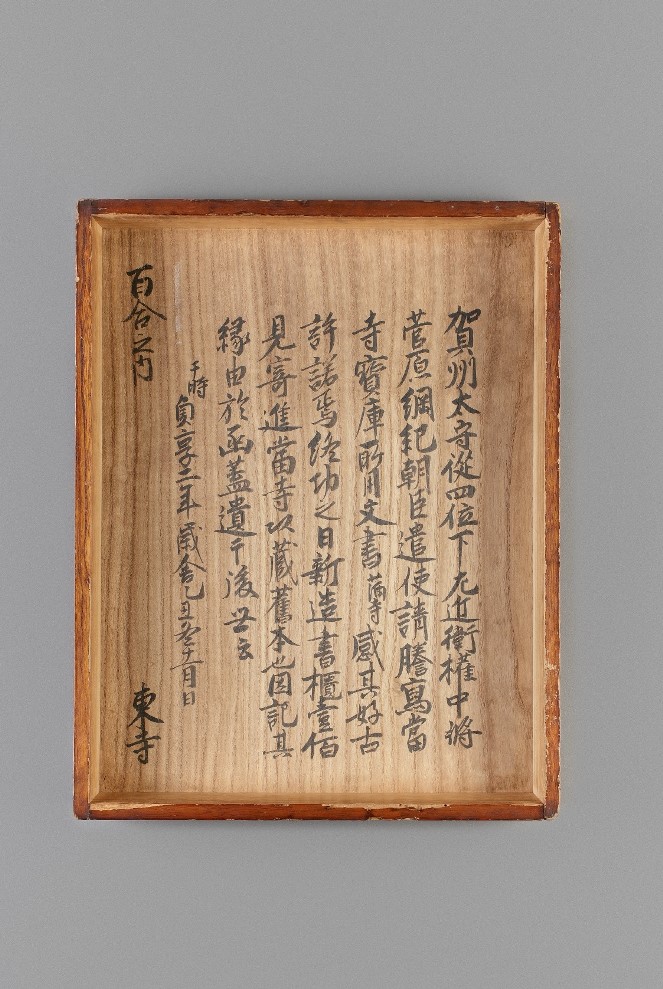

By the way, the Hyakugo Archives were so named after the 100 boxes donated to Toji by Maeda Tsunanori (前田綱紀), the fifth lord of Kaga-han (feudal domain of Kaga). What motivated him to donate these boxes? Tsunanori collected ancient documents that had been owned by the Imperial Court, the bakufu (shogunate), court nobles, feudal lords, and shrines and temples in various places. He borrowed ancient documents and had them copied. Before he returned those documents to their owners, he created boxes or other protective containers for documents that might be lost or eaten by worms, with consent of the owners, to show his appreciation. Besides the boxes of the Toji Hyakugo Archives, famous works by Tsunanori include the repair of the collection of books owned by the Sanjonishike noble family, and the renovation of their library. In the precincts of Kanazawajo (金沢城), Tsunanori’s castle, there was a workshop called “Osaikusho (御細工所)” for weapons and various traditional craft products. It is recorded that dexterous samurai warriors and craftsmen from the town were trained to acquire and improve techniques. The Kiribako of the Hyakugo Archives are also considered to have been made in this Osaikusho.

In this way, Tsunanori was a wise lord who contributed to the promotion of traditional handicrafts in his domain, and to the collection and preservation of cultural properties in various places. The Hyakugo Archives would not have existed without the 100 boxes donated by him. It could be said that Tsunanori was the man of the largest merit for the recommendation of the Toji Hyakugo Archives to the Memory of the World list.

(Machiko Matsuda, the Kyoto Institute, Library and Archives)