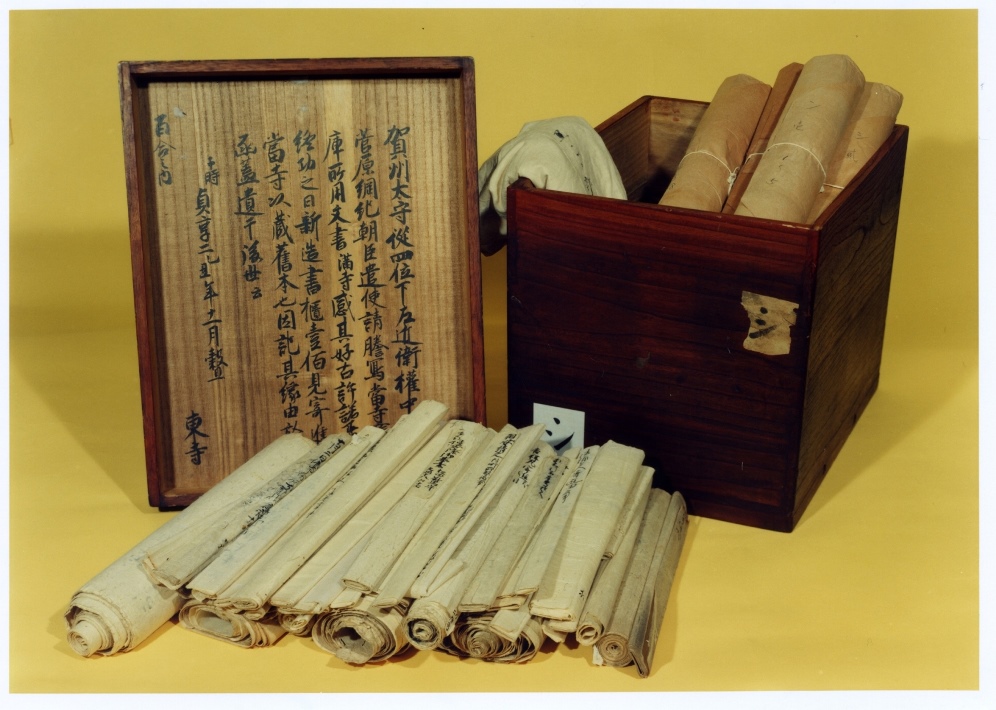

Today’s story behind the Hyakugo Archives is not about the content of the documents, but about the Kiribako (boxes made of paulownia wood) that contain them.

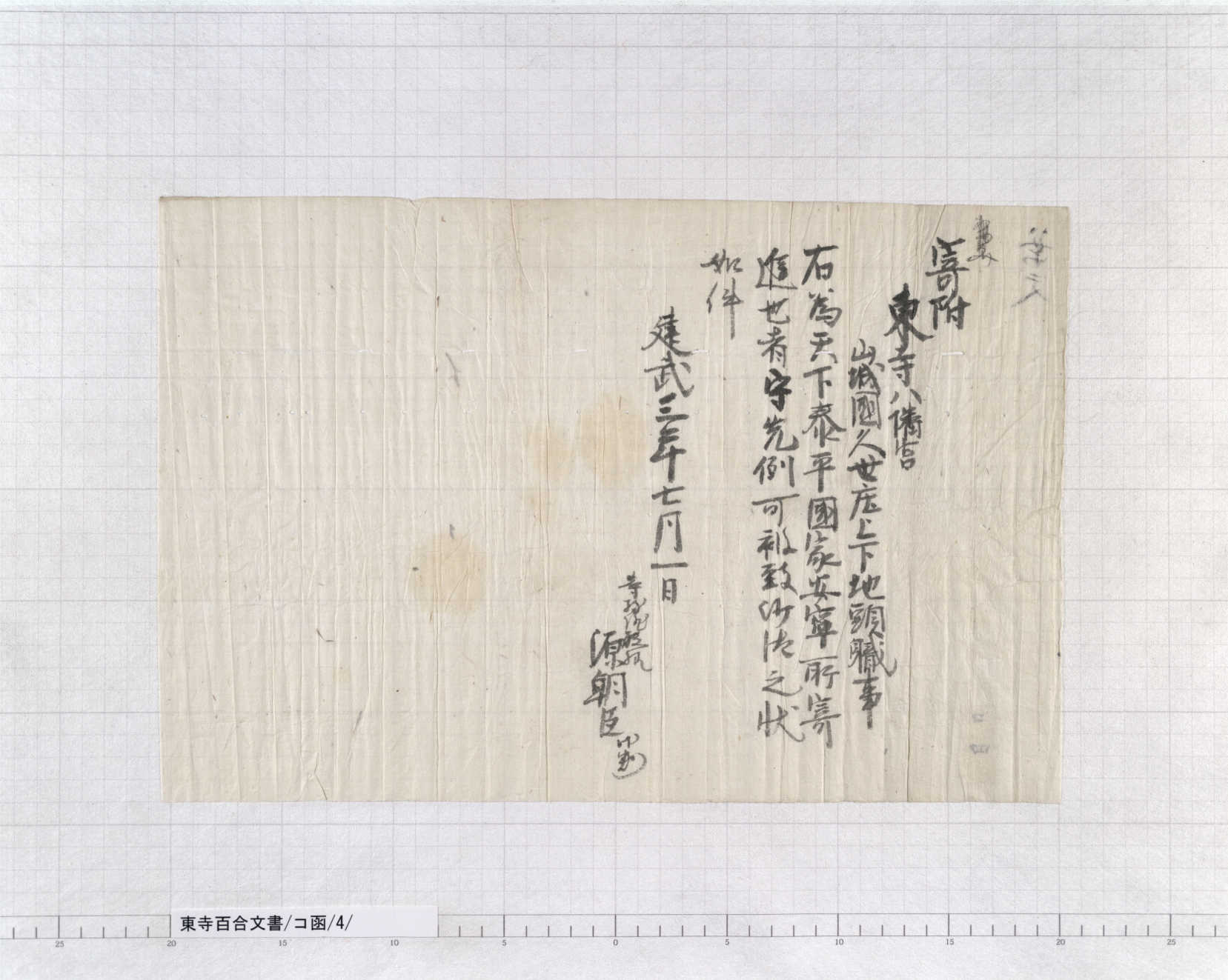

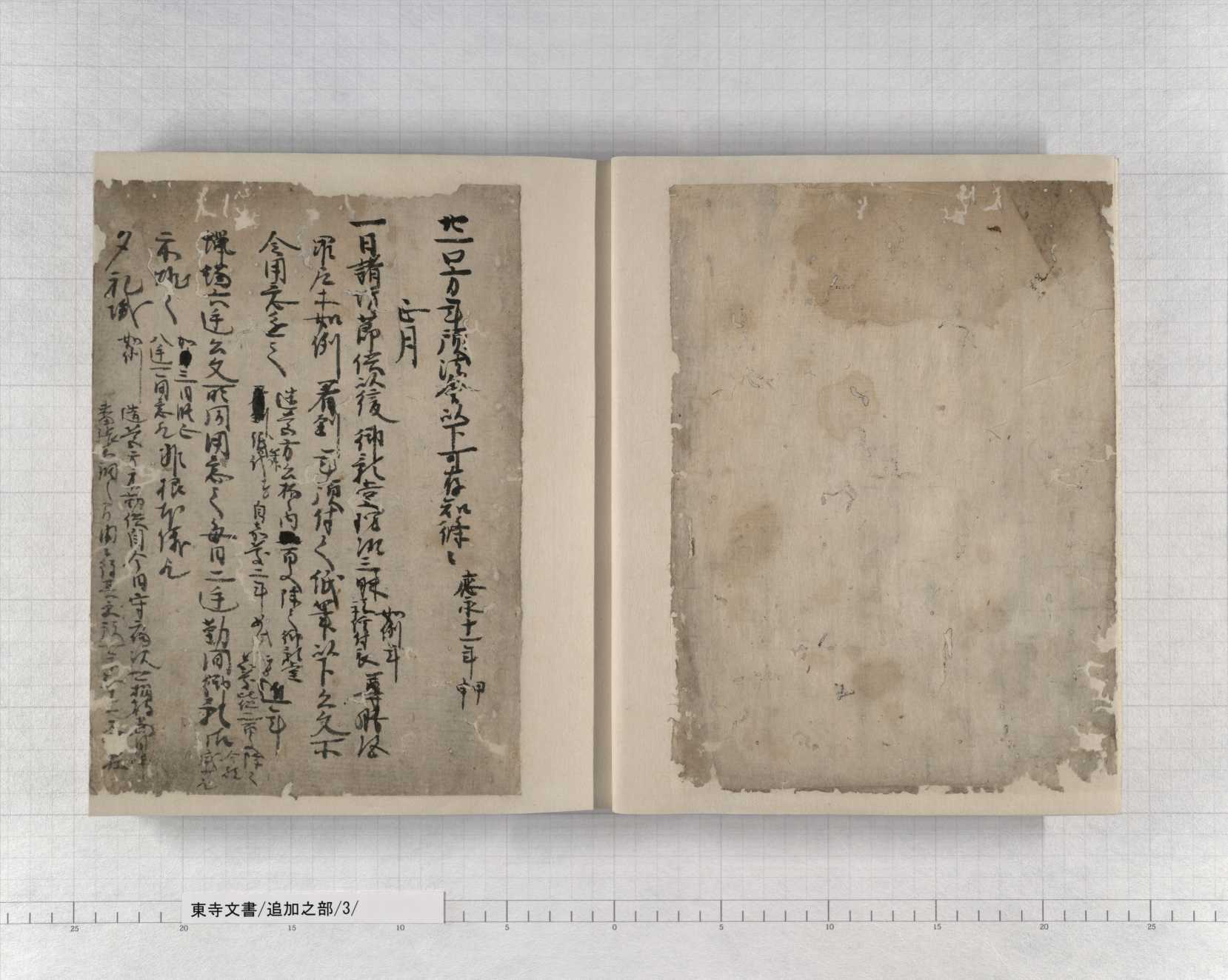

Ashikaga Takauji(足利尊氏) narrowly won the battle, thanks to the protection of the Toji Chinju-Hachimangu shrine(東寺鎮守八幡宮). However, fights continued in Kyoto and in Hieizan (Mt. Hiei), and the war situation was unpredictable. As Takauji keenly wanted to achieve his fervent wish, he contributed an estate of his to Toji Chinju-Hachimangu on the day following the “release of sacred arrows by the deity”, praying for further protection.

Continue reading Prayer for victory – Contribution from Kuze Kamishimonosho Jitoshiki

The Todaimon(東大門) gate quietly stands to the northeast of the five-storied pagoda of Toji. Todaimon is also called “Akazunomon(不開門) (lit. never-opened gate)”. As its name suggests, the doors of this gate are not opened except on special occasions. Do you know why?

Continue reading Guards of Toji: the Akazunomon gate and the Toji Chinju-Hachimangu shrine

Kobo Daishi Kukai (弘法大師空海)(774 – 835) was the founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, and has been worshipped by a large number of people even after his death. Numerous picture scrolls have also been created depicting his life and profile.

Stone pagoda unearthed near the site of the Rajomon gate, owned by the Museum of Kyoto

* This image is not provided with a CC BY license.

An excavation in 1961 unearthed a stone pagoda near the presumed site of the Rajomon gate (羅城門), close to Toji Temple. On this stone pagoda, the following letters were recorded:

天正八年

(Sanskrit alphabet “Ā”) 権僧正亮祐大和尚位 (Gonnosojo Ryoyu Daiwajoi)

壬三月十八日

Continue reading Ryoyu, a Buddhist monk recorded on a stone pagoda

The Onin War refers to a battle that started in 1467 and continued for about a decade, fought in Kyoto by the eastern army and western army of military governors. It is recorded in “Nijuikku-kata Hyojo Hikitsuke” (Box Hiragana CHI, No. 19) that Toji Temple sent its treasures and documents to the Daigo-ji Temple (醍醐寺) for shelter in September 1467, shortly after the war started, for the purpose of protecting them from the fires of war. “Nijuikku-kata” (廿一口方) refers to an in-house organization of Toji Temple in medieval times, which consisted of 21 monks. “Hikitsuke” (引付) means minutes of meetings (“Hyojo”) held by such organizations.

When Toji brought disputes to court presided by Miyoshi Nagayoshi (三好長慶) in the Sengoku period, they concluded an agreement for consultancy with Yasui Soun (安井宗運), for the purpose of enabling efficient proceedings. Therefore, Soun, as the representative of Toji visited Matsunaga Hisahide (松永久秀) many times, a vassal of Miyoshi Nagayoshi who often handled trials involving Toji.

Continue reading Takiyamajo castle in the Sengoku period, as seen by Yasui Soun

When a dispute occurred in the Sengoku period, the Toji temple asked Miyoshi Nagayoshi (三好長慶), a powerful figure who prevailed in the Muromachi bakufu (室町幕府, Muromachi shogunate) and across the Kansai and Shikoku regions, to preside over trials.

Continue reading Sakai in the Sengoku period, as seen by Yasui Soun

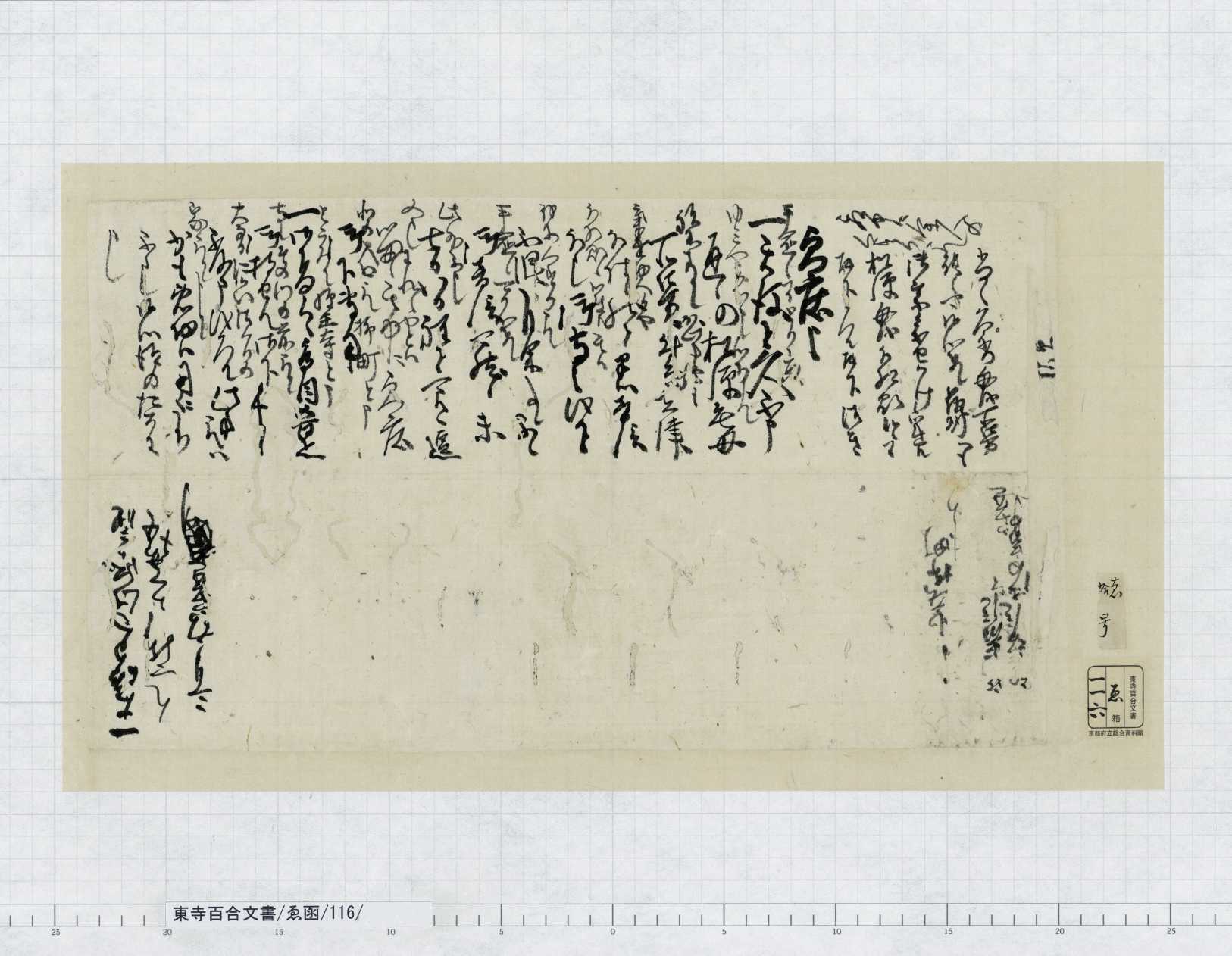

There are documents called anmon (案文). Although the word today means “a draft” in Japanese, anmon is actually a manuscript copy of shomon (正文, the original document). Anmon was not only kept as a spare, but also used in a wide range of situations.

Continue reading The functions of anmon: Copies as valid as the originals

Monks who were assigned to protect the statue of Kukai (空海) at Sai-in Mieido (西院御影堂) were called hijiri (聖). They were also called sanshonin (三聖人, lit. three saints) as the quota of hijiri was three. The position of hijiri is believed to have been established when the statue of Kukai was enshrined in Sai-in Kyozo (西院経蔵, Sai-in Library) in 1233.

Continue reading “Hijiri”: monks who supported the management of documents

Kuso (供僧) refers to a group of monks of Toji who were allowed to attend hyojo (評定, meetings) and conduct Buddhist services as members of monastic organizations, including Nijuikku-kata (廿一口方), Gakushu-kata (学衆方), and Chinjuhachimangu-kata (鎮守八幡宮方). The prescribed number of kuso varied depending on the organization, and a new kuso monk was chosen only when there was a vacancy.

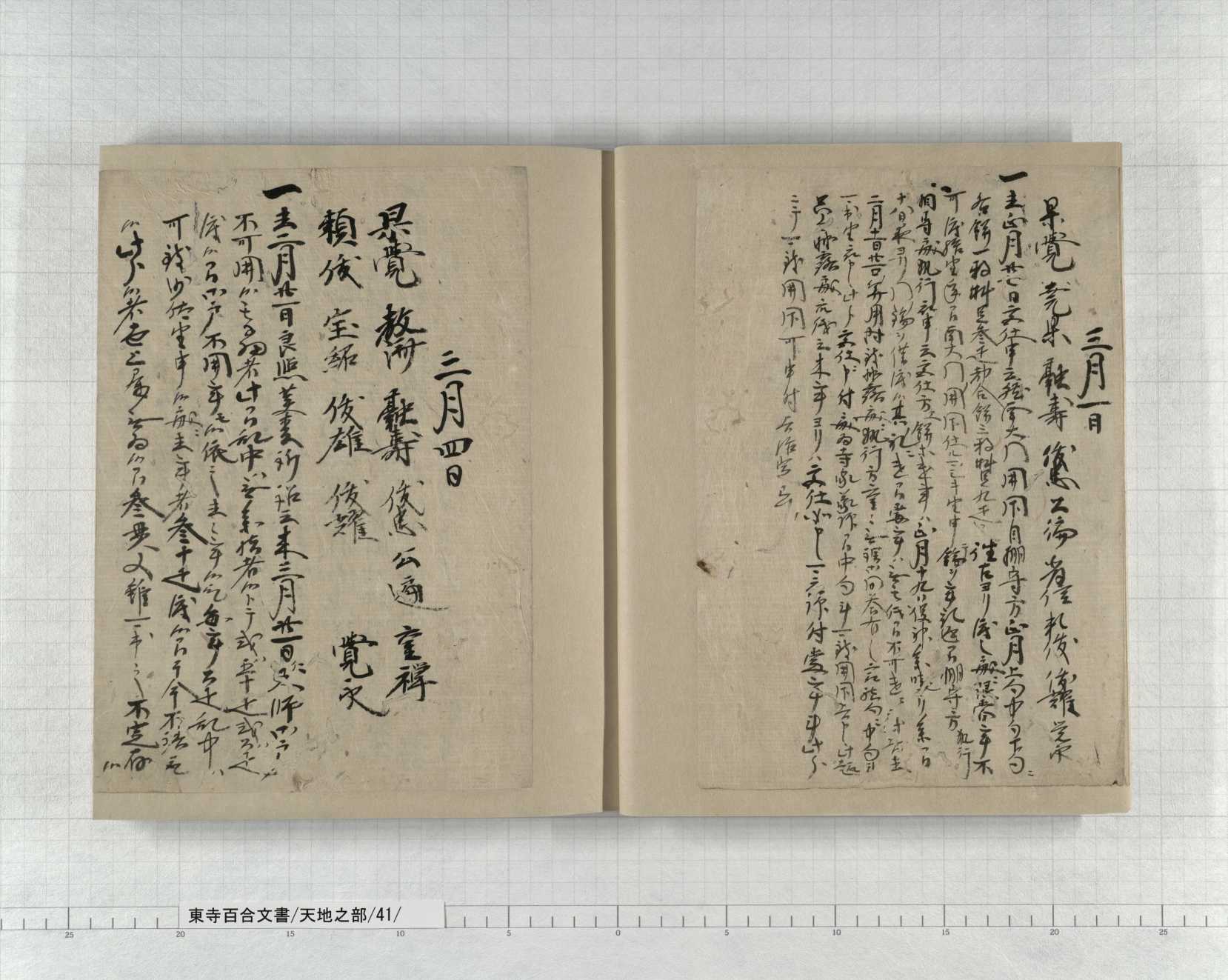

Hyojo-hikitsuke (評定引付), records of meetings organized by kuso (供僧) monks, allows us to understand the situation of Japanese society in medieval times.

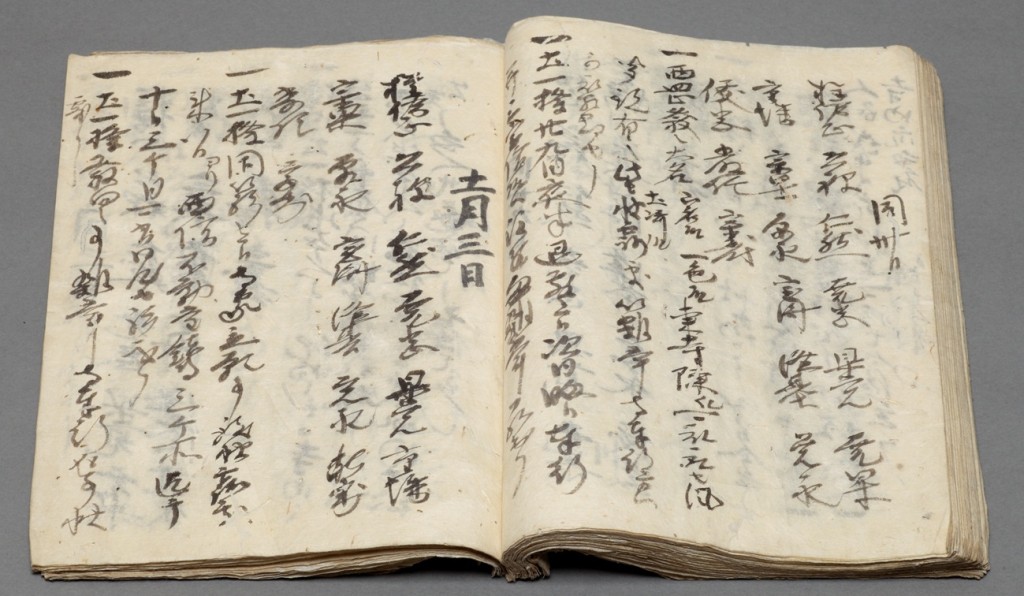

The hyojo-hikitsuke above was written by kuso monks of Nijuikku-kata (廿一口方) around when the Onin and Bunmei War ended. The chapter of March 4, 1478, states that when the country was at peace, in other words, when there was no war, Toji collected 40-50 kanmon in offerings a day, and that the number of visitors was expected to increase on sunny days. This allows us to presume that Toji was worshipped by a great number of people crowding the premises of the temple.

Continue reading Hyojo-hikitsuke reveals Japan of medieval times

Each monastic organization within Toji had a leader called nengyoji (年行事, also called bugyo “奉行” or nenyo “年預”.) The nengyoji was chosen from among kuso monks, the leading members of the organization, and assumed responsibility for operating the organization for a year.

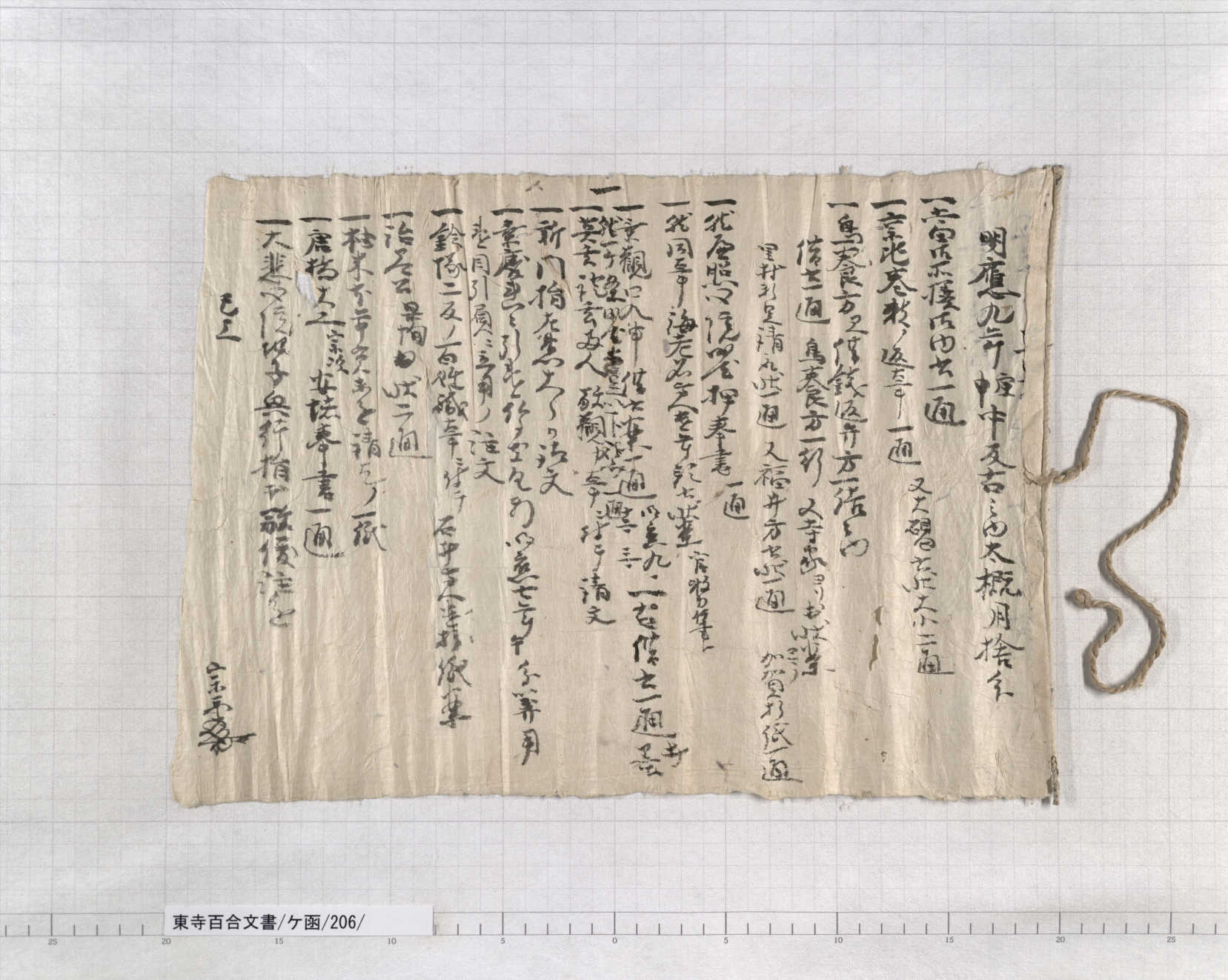

The document above, written in 1500, is a list of documents the bugyo of Nijuikku-kata planned to discard but decided not to. Sorting out documents to preserve from a large number of documents brought from inside and outside the organization was one of the bugyo’s duties. The documents preserved in the Sai-in Library were a few that had survived the selection by the successive bugyo.

The list includes 24 documents, 17 of which are extant today.

The documents housed in Sai-in Bunko (西院文庫, Sai-in Library) of Mieido (御影堂) were sometimes removed from the library to study previous precedents or to use as evidence at trial. Any person who removed documents from the library was required to write his signature in a book called “Sai-in Bunsho Suito-cho (西院文庫出納帳),” which still provides details of what documents were removed and returned by whom 500 years ago.

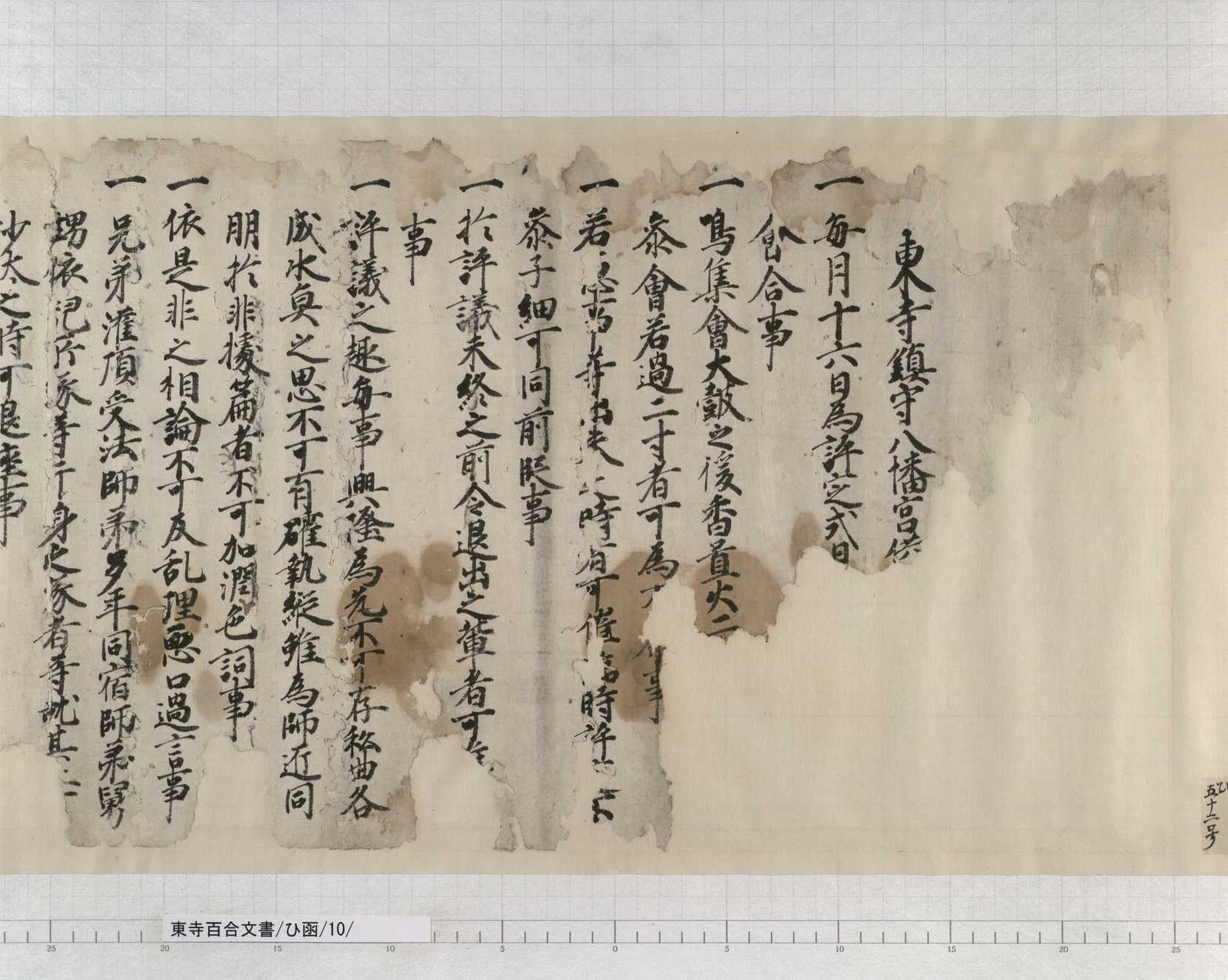

The monastic organizations established within Toji were operated independently and each organization decided important matters in meetings called hyojo (評定). The documents of Hyakugo Monjo show how hyojo was organized by leading members of the organization, who were referred to as kuso (供僧).

Continue reading The rules of hyojo: Being late or absent was prohibited

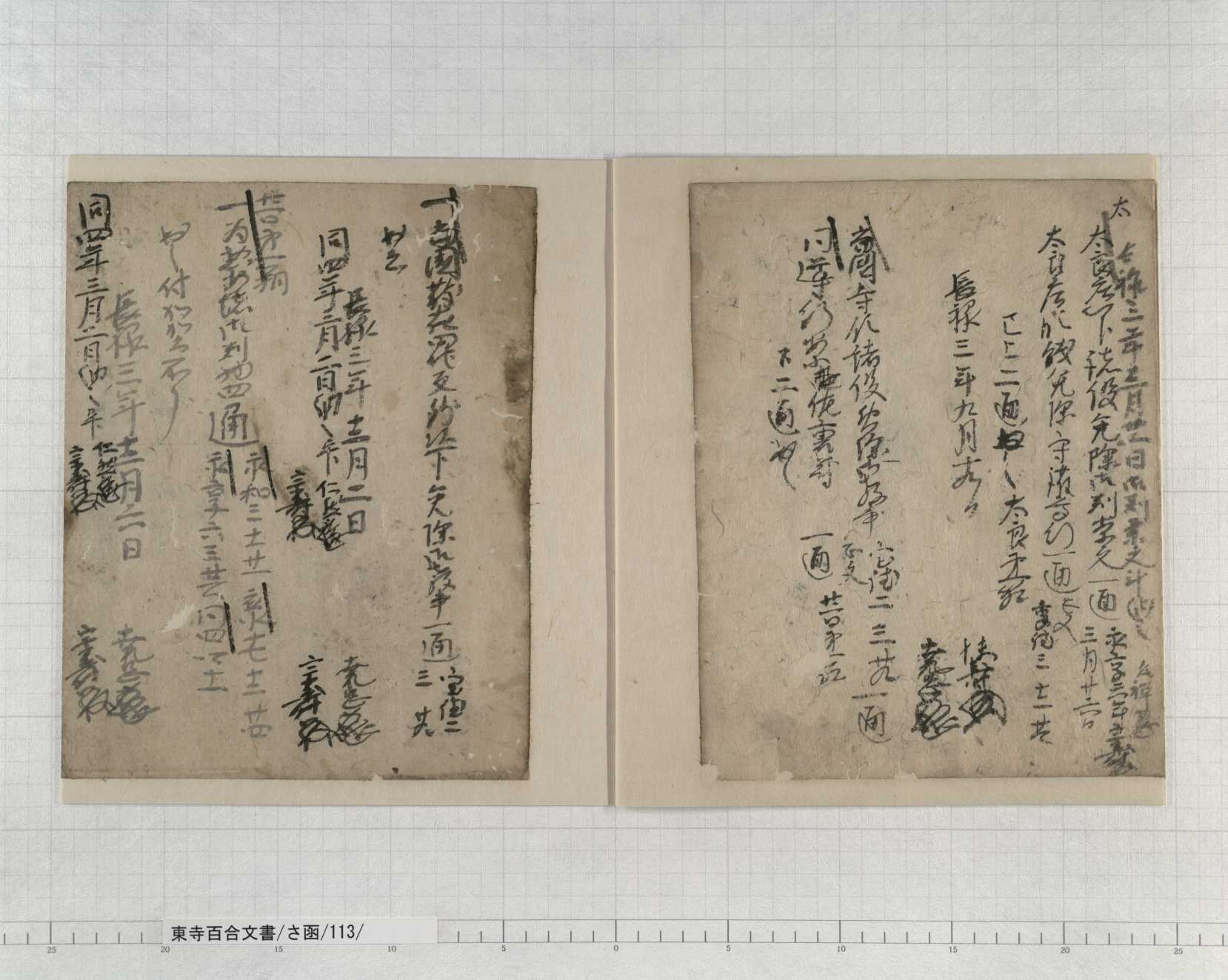

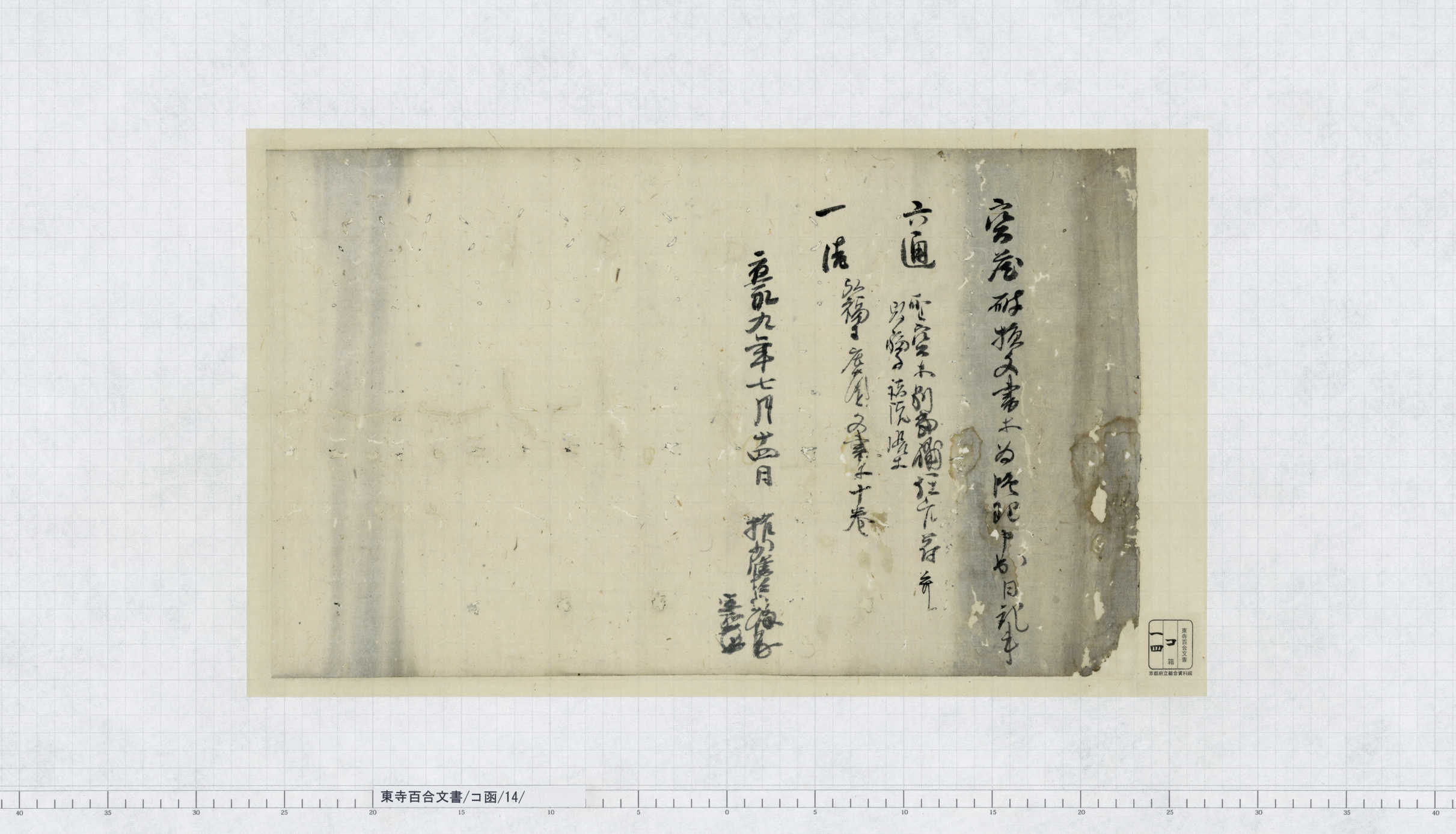

The document above is a record of documents removed from the treasure house for restoration work in 1402, around the middle of the Muromachi period. The document reveals that six documents and a bound book were removed from the treasure house. One of the six documents was “Shobo-betto Bunin-kanpu (聖宝別当補任官符),” an official document appointing Shobo, a monk who founded Daigo-ji Temple, to a position called bonso-betto (凡僧別当, head monk) of Toji in 902. Toji had preserved this 500-year-old document and restored it for future use. Toji had a strict management system to preserve and utilize its documents.

Toji Hyakugo Monjo is a collection of “ancient documents.”

You may think of ancient documents as old pieces of paper on which undecipherable kanji characters have been written with a brush and India ink.

You may also think that reading ancient documents requires a great deal of knowledge and effort because you will need to decipher each character in cursive form and look up every word you do not understand in a dictionary.