Kobo Daishi Kukai (弘法大師空海)(774 – 835) was the founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, and has been worshipped by a large number of people even after his death. Numerous picture scrolls have also been created depicting his life and profile.

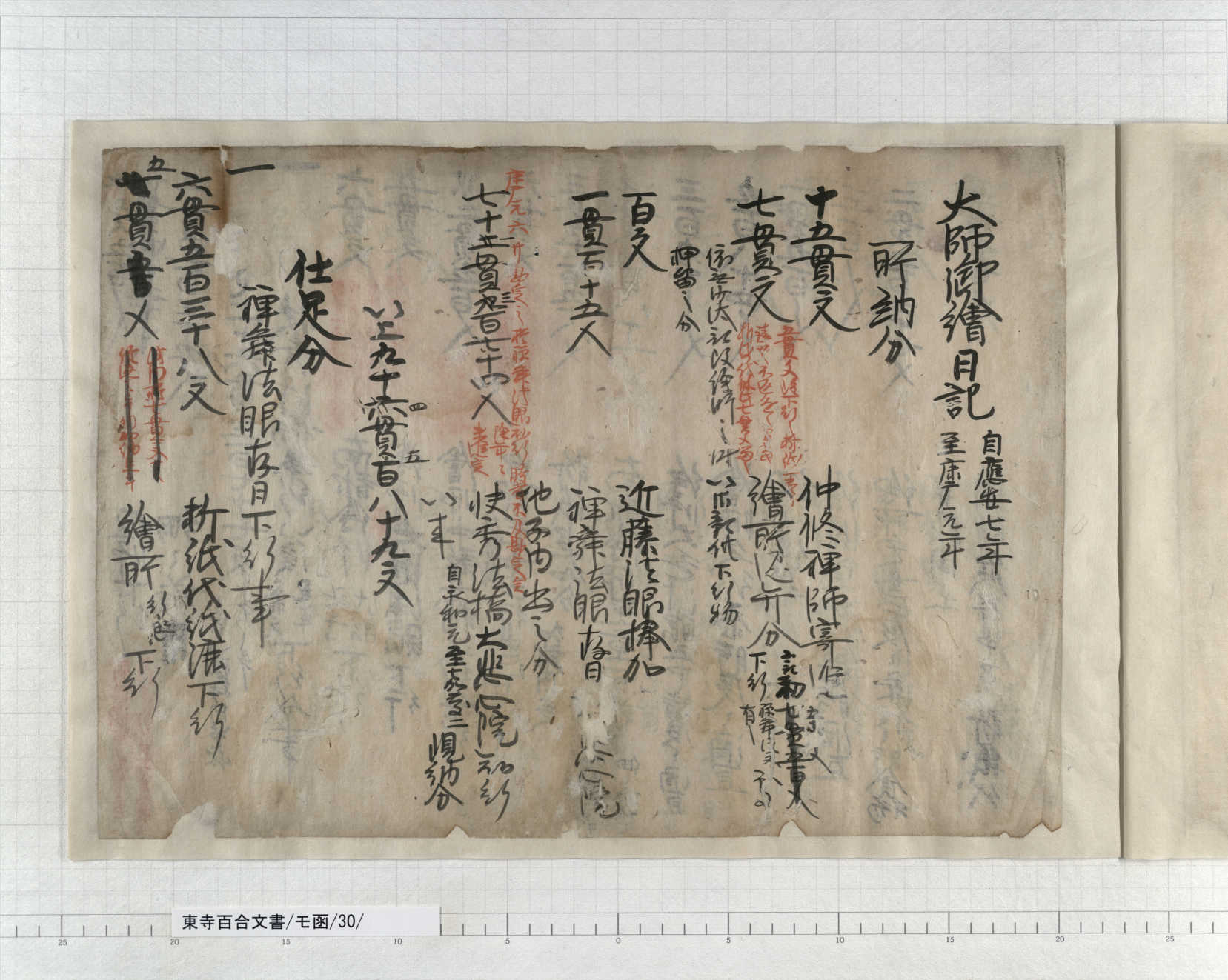

In particular, “Kobo Daishi Gyojo Ekotoba (弘法大師行状絵詞) (lit. pictorial description of acts by Kobo Daishi)”, a national important cultural property that has been owned by Toji Temple is a wonderful work that consists of 12 volumes. The formulation of these picture scrolls was planned in 1374, the 600th anniversary of the birth of Kobo Daishi. This must have been an important commemorative project for Toji Temple. The Toji Hyakugo Archives include a document titled “Daishi On-e Yoto Chumon” (大師御絵用途注文), with relation to the formulation of these picture scrolls.

What does “Daishi On-e Yoto Chumon” mean?

Today, “Yoto” (用途) means purpose of use and “Chumon” (注文) signifies requesting something from someone. In the medieval times, “Yoto” meant expenses required, and “Chumon” signified recorded requirements concerning a certain matter.

Therefore, “Daishi On-e Yoto Chumon” means a record or specification of various expenses that were spent on the formulation of the picture scrolls (“On-e” (御絵)).

This record reveals a lot of information concerning the time when these scrolls were established, painters involved in this project, expenses for paper and paints, etc.

At first, Toji commissioned this project to Koseno Yukitada (巨勢行忠), the top painter who was under the direct control of the Imperial Court (“Edokoro” (絵所)).

Although Yukitada received remuneration, he was slow to initiate the work. Consequently, Yukitada was ordered to pay back the remuneration, and three other painters were convened in place of him.

The job of painter (“Eshi”(絵師)) in those days was slightly different from that in the present day. Rather than drawing pictures that they liked, Eshi were hired by the bakufu, Imperial Court, or temples and shrines, and drew pictures on Byobu (folding screens) and Fusuma (sliding doors), and created portraits, as ordered by their employers.

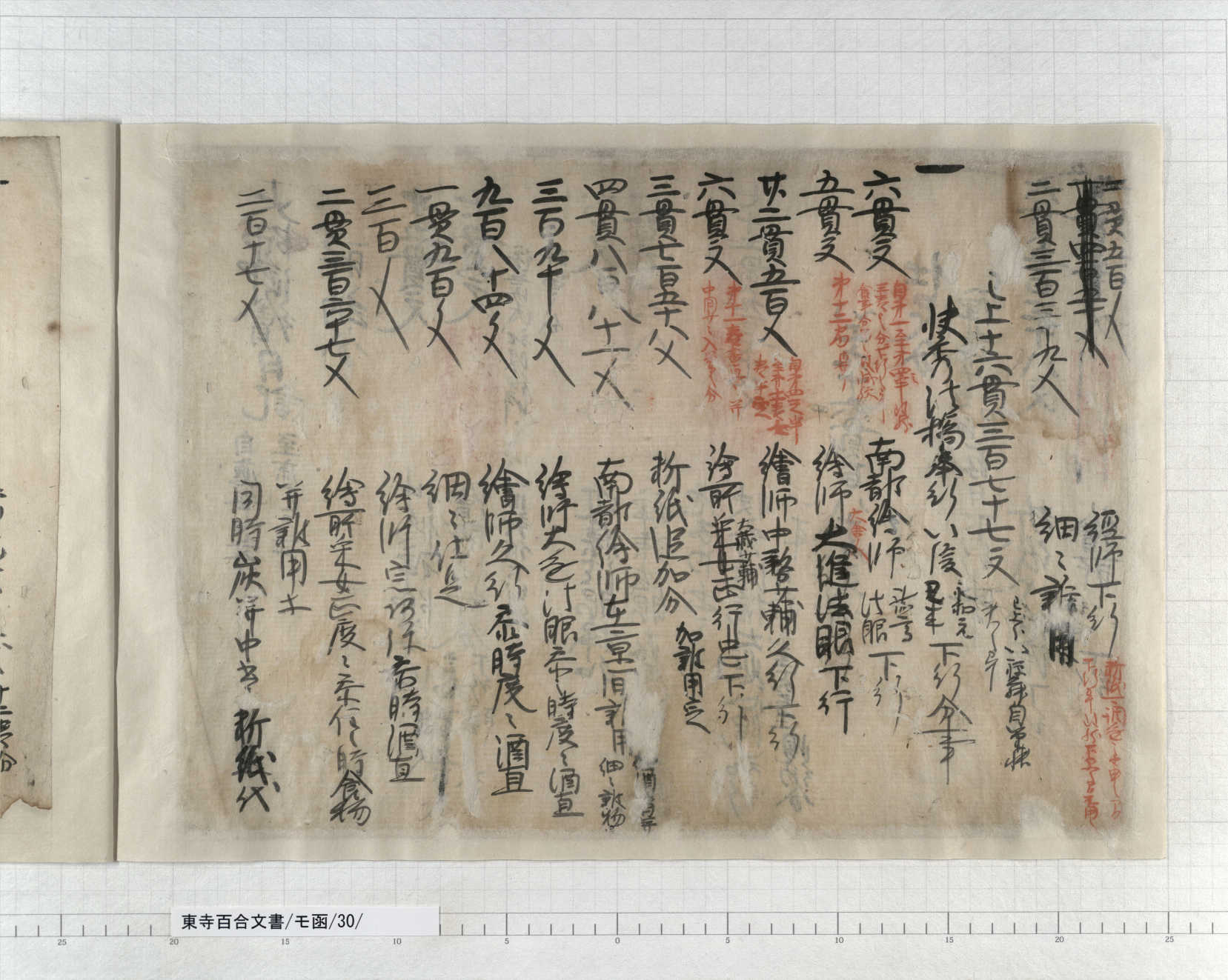

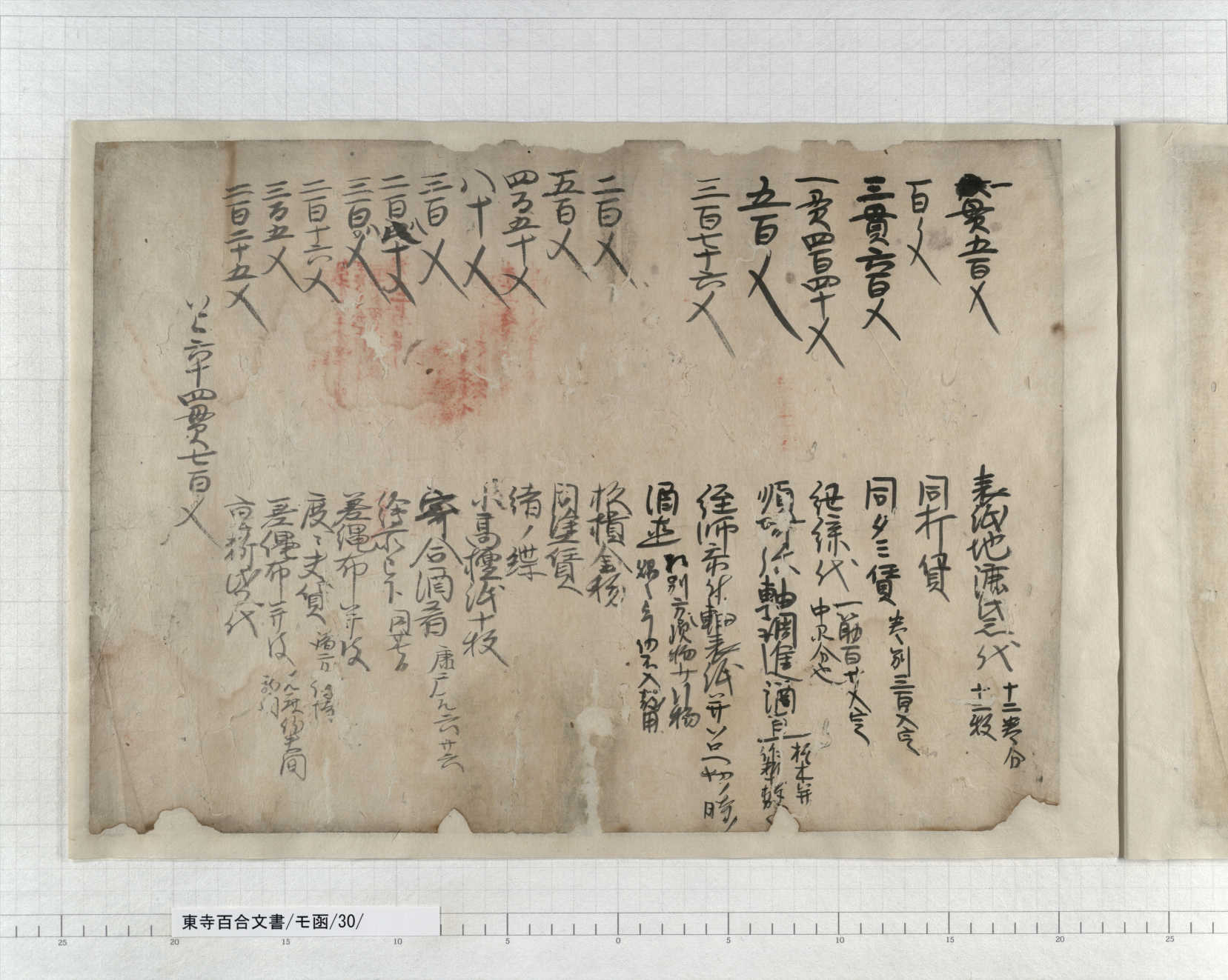

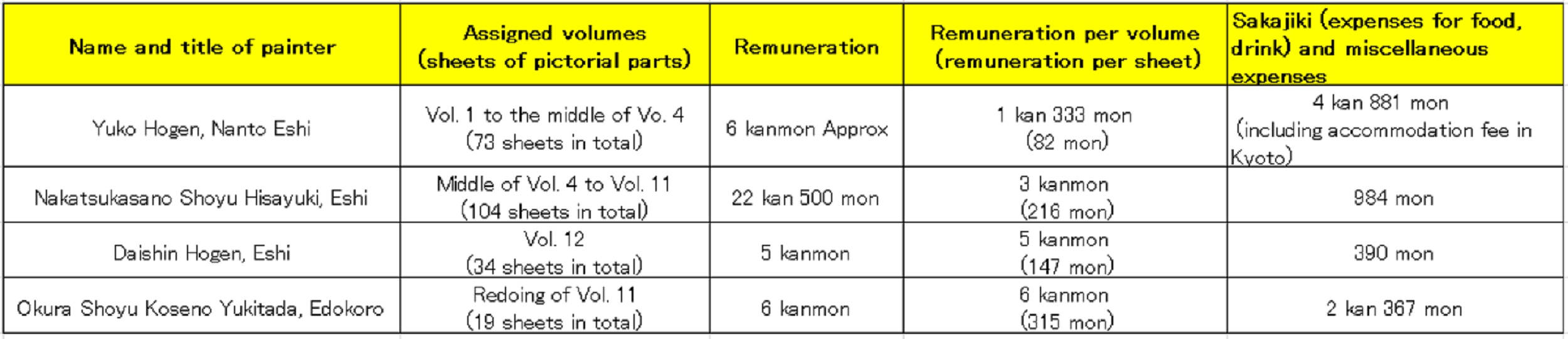

The world of art in those days was no less severe then that in the present times, and the rating of painters was clearly reflected in their wages. The wages of the four painters, including Yukitada, who returned to the project staff later, varied substantially.

Look at the table below, formulated based on this record:

It was Yuko, who was hailed from Nara, who received the lowest wage. While he had small expenses including accommodation fee in Kyoto covered by Toji Temple, he only received 6 kanmon in total as remuneration for painting from Vol. 1 to the middle of Vol. 4.

In contrast, Yukitada merely redid Vol. 11 and touched up the entire work at the end of the project, receiving remuneration of as much as 6 kanmon, the same price as Yuko, in addition to the large amount of expenses for food and drink. The remuneration per pictorial page (i.e. per sheet) paid to Yukitada was nearly four times higher than that paid to Yuko.

In those days, people could buy rice of over 1 koku (equivalent to 150 kg) for 1 kanmon (equivalent to 1,000 mon).*

One adult could live on this much rice throughout one year. Therefore, 6 kanmon could feed six people for one year.

By the way, the cost of paper used for these picture scrolls stood at 6 kan 538 mon at first, but added an expense later.

The term “Sakajiki” (酒直) frequently appears throughout this record. “Sakajiki” refers to expenses for buying alcoholic drinks, so its frequent appearance indicates that drinks were served to painters on many occasions during the project.

In the year of completion of the picture scrolls, expenses for food and drink at a gathering (“Yoriai”(寄合)) were also recorded. It may have been a party to celebrate the completion of the scrolls.

Today’s drinkers might envy the medieval painters for the inclusion of drink and party fees into the expenses.

* It is difficult to figure out how much 1 kanmon would be in today’s currency.

There is a research that investigated the value of rice in the Muromachi period, based on the Hyakugo Archives and other materials.

One koku of rice was worth approximately 800 mon, with variations from year to year, according to a paper published by Kesao Momose (百瀬今朝雄), “Rice Prices in the Muromachi Period: Cases Related to the Toji Temple”, Journal of Histology, Part 66, Vol. 1, 1957.

(Matsuda, Historical Materials Section, the Kyoto Prefectural Library and Archives)