– “They say that monks send apprentices all the way to Mt. Hira for fetching their favorite foods, such as Matsutake, Hiratake, Enoki/Nameko, Renkon that grows in ponds, Seri, Junsai, Gobo, Kohone, Udo, Warabi, Tsukushi, and so on.”

This is from Volume 2 of the “Ryojin Hisho(『梁塵秘抄』)” poetry anthology, which was compiled in the late Heian period, collecting songs of the “Imayo(今様)” style. This anthology covers diverse aspects of life of nobles, monks and common people.

The quotation above is translated from one of the songs included in Ryojin Hisho, naming Matsutake before everything else as the favorite food of monks! It seems that the Matsutake mushroom has been loved as the most popular fall delicacy for more than 800 years.

Did monks really love Matsutake so much? In fact, the Toji Hyakugo Archives contain many pieces of evidence of this.

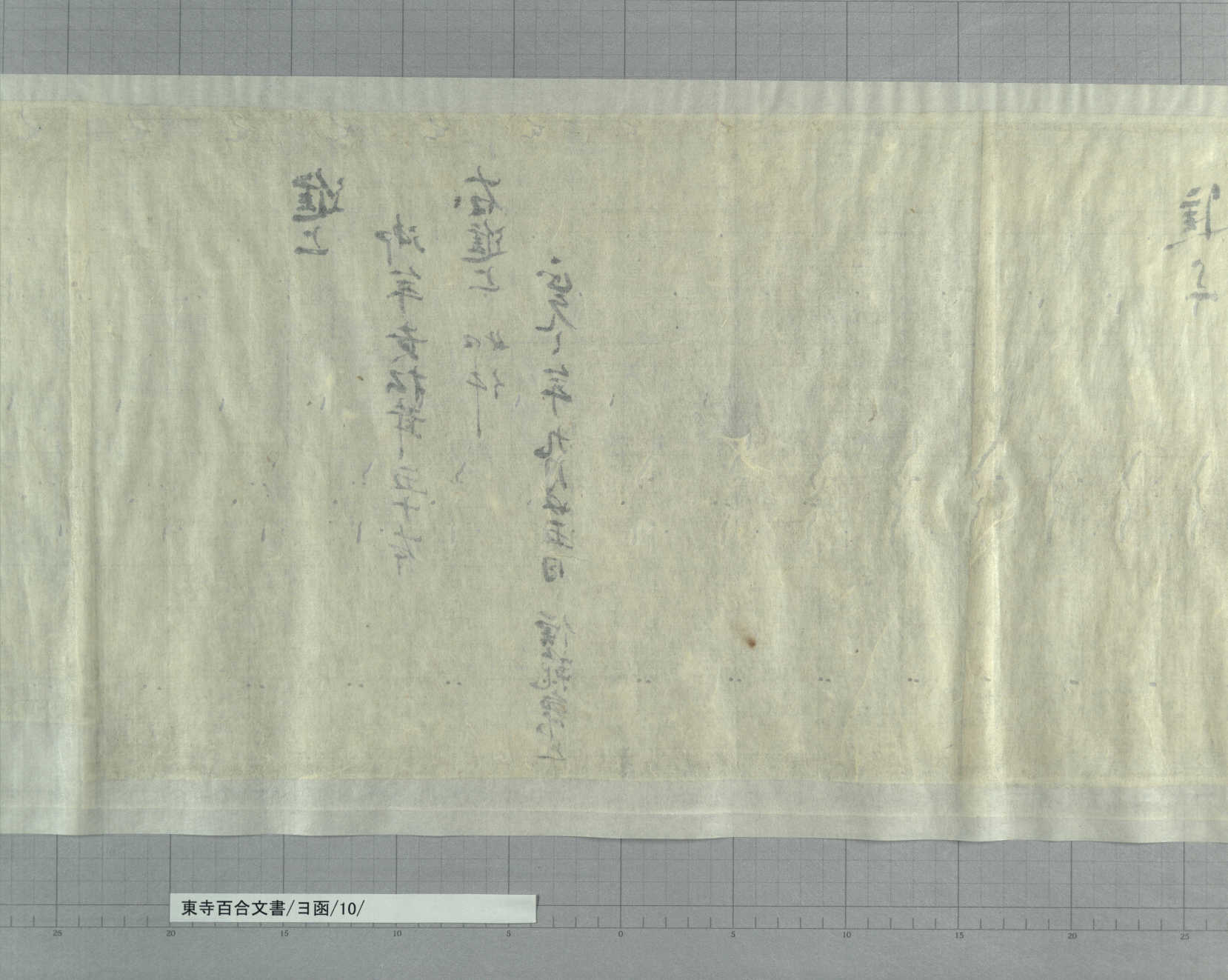

When fall came, Matsutake was delivered to Toji as land tax in early September (around October in the present calendar) every year. The document below is a letter attached to Matsutake that was sent from Yamatonokuni Hiranodonosho(大和国平野殿荘), which was located around Ikoma, Nara Prefecture:

The letter says that they deliver 90 pieces of Matsutake as usual, and asks monks to offer them to Kobo Daishi(弘法大師) before dividing among monks. Offering to Kobo Daishi before dividing among monks indicate how importantly Matsutake was handled in those days.

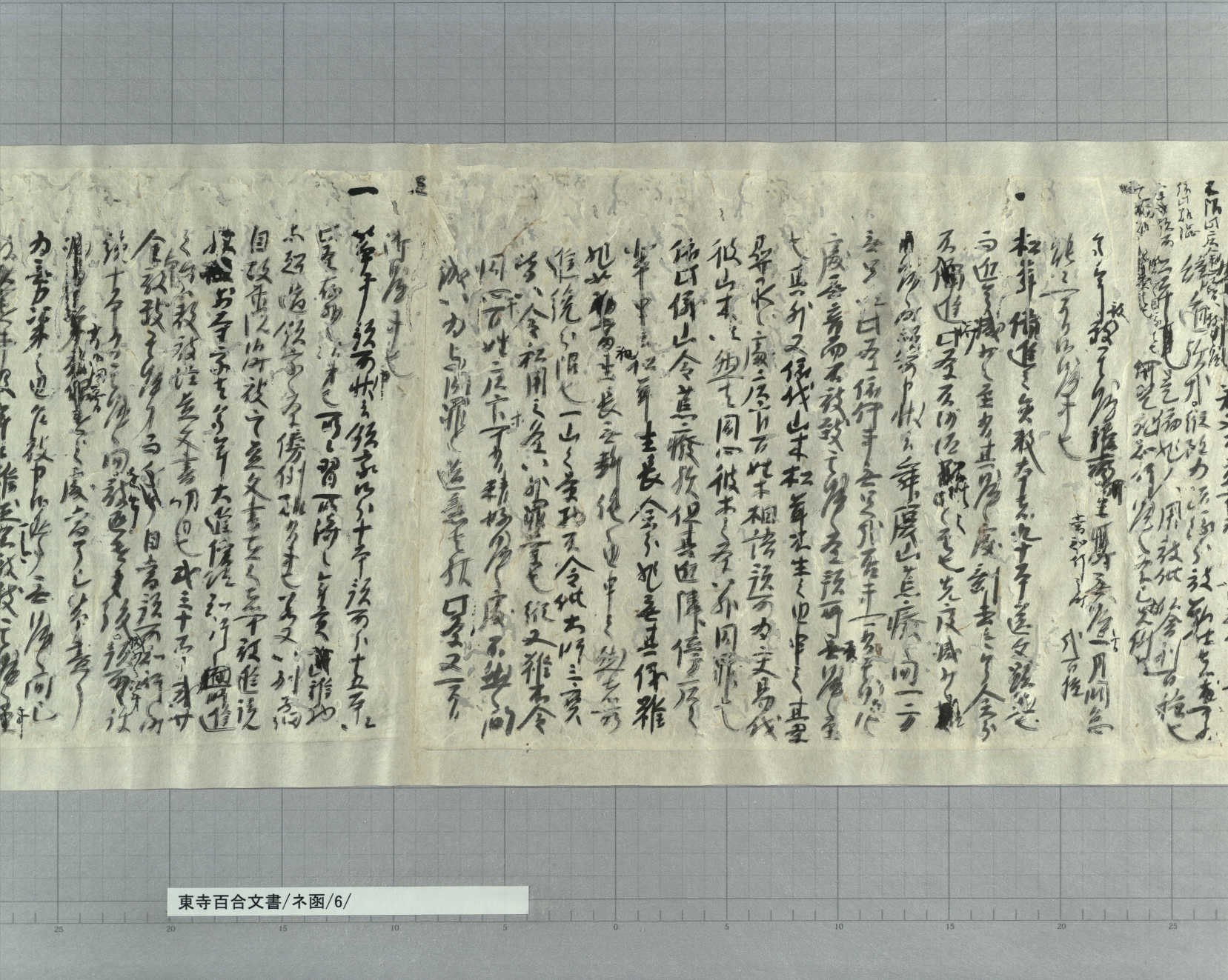

The document below was written by Kumon(公文), a person in charge of distributing land tax from Shoen (manors). It also contains reference to Matsutake delivered as land tax:

In this document, it is stated that Matsutake sent from Hiranodonosho was “一山之景物”, and that it was particularly sinful to acquire it without offering to Kobo Daishi. “景物” means a rare seasonal specialty from mountains. It seems that fragrant Matsutake was handled not as ordinary food, but as a special offering.

In “Kefukigusa(毛吹草)”, a book written in the early Edo period, special products from different parts of Japan are listed. In the section of Yamato(大和) (present Nara), Matsutake is included in the list (Volume 4, Kefukigusa). Matsutake that was delivered from Hiranodonosho, Yamato, must have been valued very highly.

Matsutake was loved not only by monks. In Toji, Matsutake sent as land tax was not enough. They bought additional Matsutake for high prices, and served it in parties, or presented it to temples that had close ties with Toji, to Shogun, and to other important figures in Bakufu (shogunate). It was often included in the meeting agenda to whom Matsutake should be presented, and how much the amount should be (Item 12 of Box-CHI (Hiragana), “Nijuikku-kata Hyojo Hikitsuke”, Article dated September 18, 1438, and others).

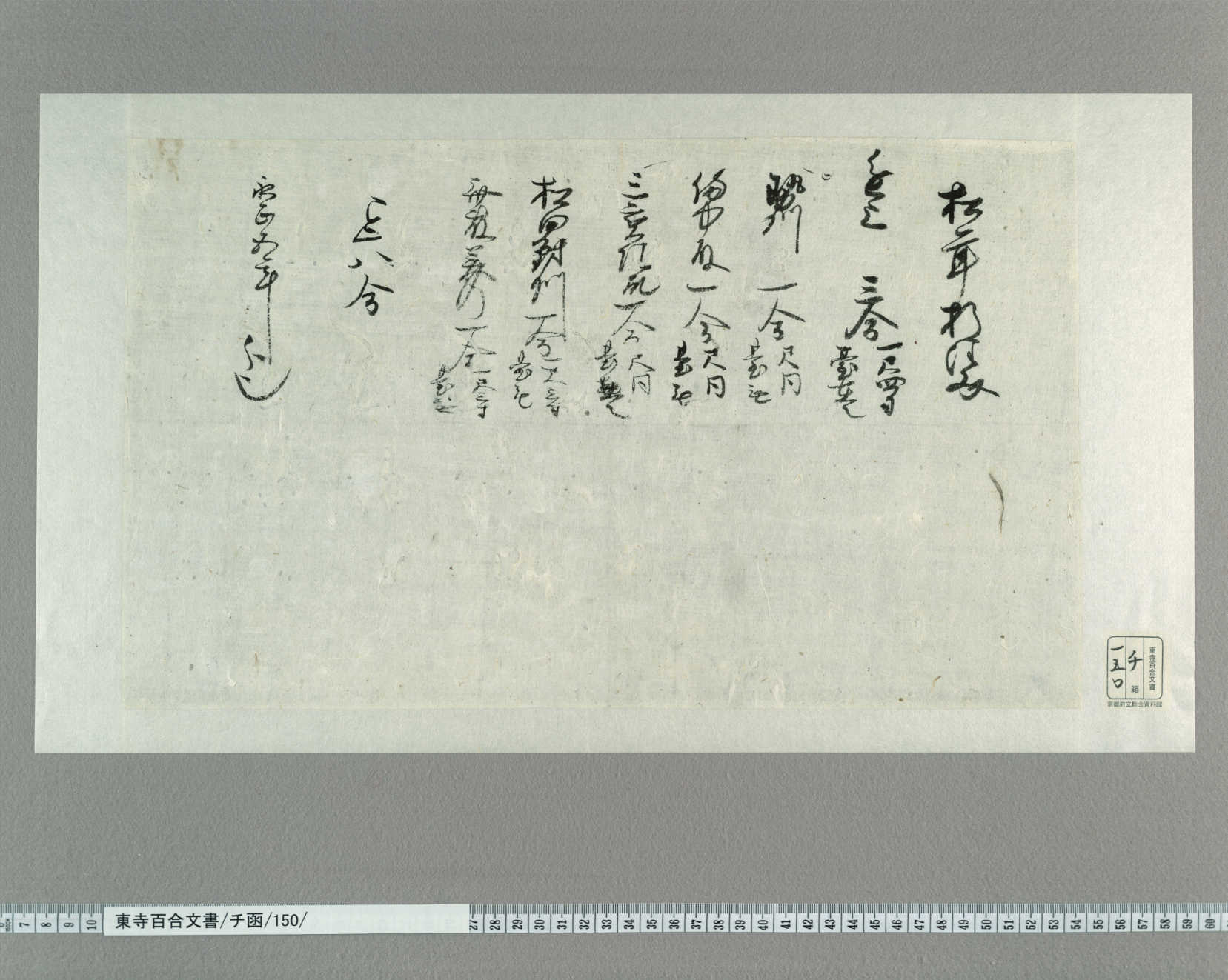

The following document indicates what kinds of boxes were used for presenting Matsutake:

This document lists to whom Matsutake would be presented, and specifies the respective numbers and sizes of boxes. For example, in the second line it says “進上 三合”, and underneath it is written “一尺四寸 台在之”. “進上 (Shinjo)” here means that Matsutake was presented to Ashikaga Yoshitada(足利義尹), the 10th Shogun of the Muromachi bakufu. “合 (Go)” is a unit used for boxes, just as in the Toji Hyakugo Archives. One Go means one box. In this case Matsutake was presented in three square boxes with bases, about 42 centimeters on one side. The document shows that one box each was also presented to five other persons, making eight boxes in total. Boxes to other persons were smaller and without bases, suggesting that the gift to Shogun was particularly special.

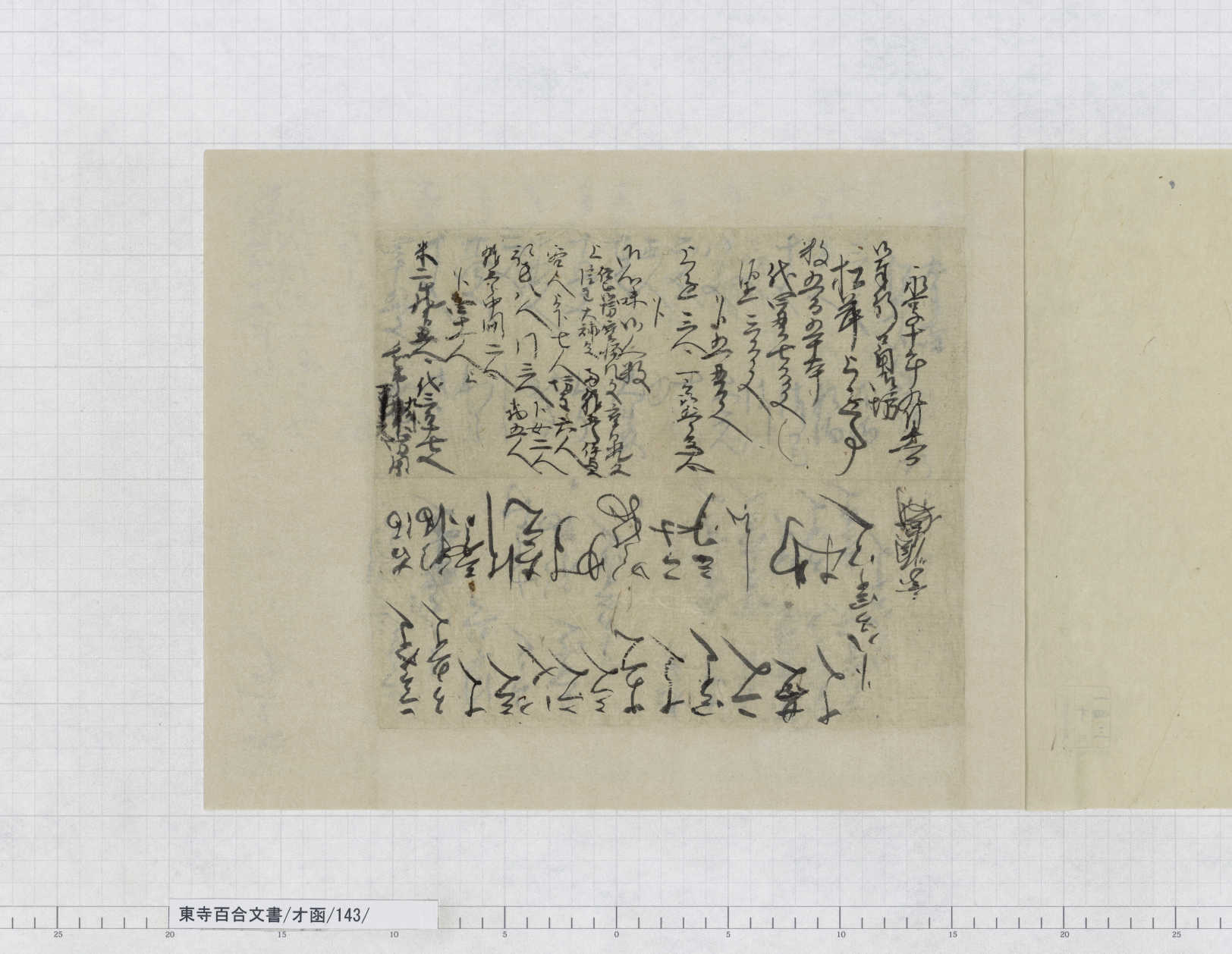

Today, Matsutake grown in Japan is priced as high as around 10,000 yen per piece. It would be extravagant to present eight boxes of them! How much did it cost in those days? Look at the document below:

At the beginning, it is written “松茸上進事”, followed by the specification “数五百五十本 代四貫七百文”. As many as 550 pieces were donated! According to the price indicated here, one piece cost approximately 8.5 mon. At the top left of this document, it says “米二斗九升五合 代三百十七文”, indicating that rice cost approximately 7.3 mon per kilogram at that time. So, a piece of Matsutake was slightly more expensive than one kilogram of rice. It seems much more reasonable than in the present day. In those days, there were many pine (Matsu) mountains around Kyoto, and the harvest of Matsutake was much larger than in the present.

“心味 (Kokoromi)” in the title of this document signifies the tasting of a food. Maybe people had a party for enjoying Matsutake together as a seasonal specialty of fall. In the lower half of this document are listed food items served at this party, and seasonings used for them. Vintage sake, new brew of sake, rice, Japanese white radish, ginger, pickled vegetables, kelp, soybean paste, salt, vinegar, etc. It is clear that Matsutake was the special feature of the party, but unfortunately the document does not reveal how it was cooked and served.

It seems that people had a good harvest of Matsutake in this year, because it was served generously to guests and to maids. From nobles to common people must have looked forward to seasonal Matsutake every year!