On a hot summer day, we definitely want to have a break after physically demanding work.

Drinkers love alcohol, while non-drinkers do not. Would you prefer tea, or alcohol?The same discussion already existed more than 1,000 years ago, in the Tang Dynasty of China.It seems that tea and alcohol in those days slightly differed from those in our day. Apart from their tastes, both tea and alcohol have been loved by people, for their high physical and mental healing effects.

Such discussions for advocating the respective benefits of tea and alcohol were called “Shusaron (酒茶論)” or “Sashuron (茶酒論)”, and were brought from China to Japan. Since around the Muromachi period, people have enjoyed Shusaron or Sashuron through light reading materials and other humorous discussions.The same topic also started to appear in literary works, demonstrating that both tea and alcohol were widely spread and relished by people.

In fact, the popularity of tea and alcohol is also clear from the Toji Hyakugo Archives.Toji is a large temple. A lot of laborers and carpenters were collected from many places on various occasions, including cleaning, mowing, hall construction and repair, etc.On these occasions, tea, alcohol and meals were served to workers. Specifications listing the items served and expenses incurred were called “XX Chumon (XX 注文)” and “YY Gegyo Kippu (YY 下行切符)”.

Box MO (Katakana) in the Toji Hyakugo Archives contain many documents concerning the visit to Toji by Ashikaga Yoshimasa (足利義政), the 8th Shogun of the Muromachi bakufu (Muromachi shogunate), on August 22, 1462. This visit is called “Toji Onari” (Onari: visit by a noble person).In the background of the grand Onari, what food and drink were served to people who worked hard for cleaning, mowing and other preparations?

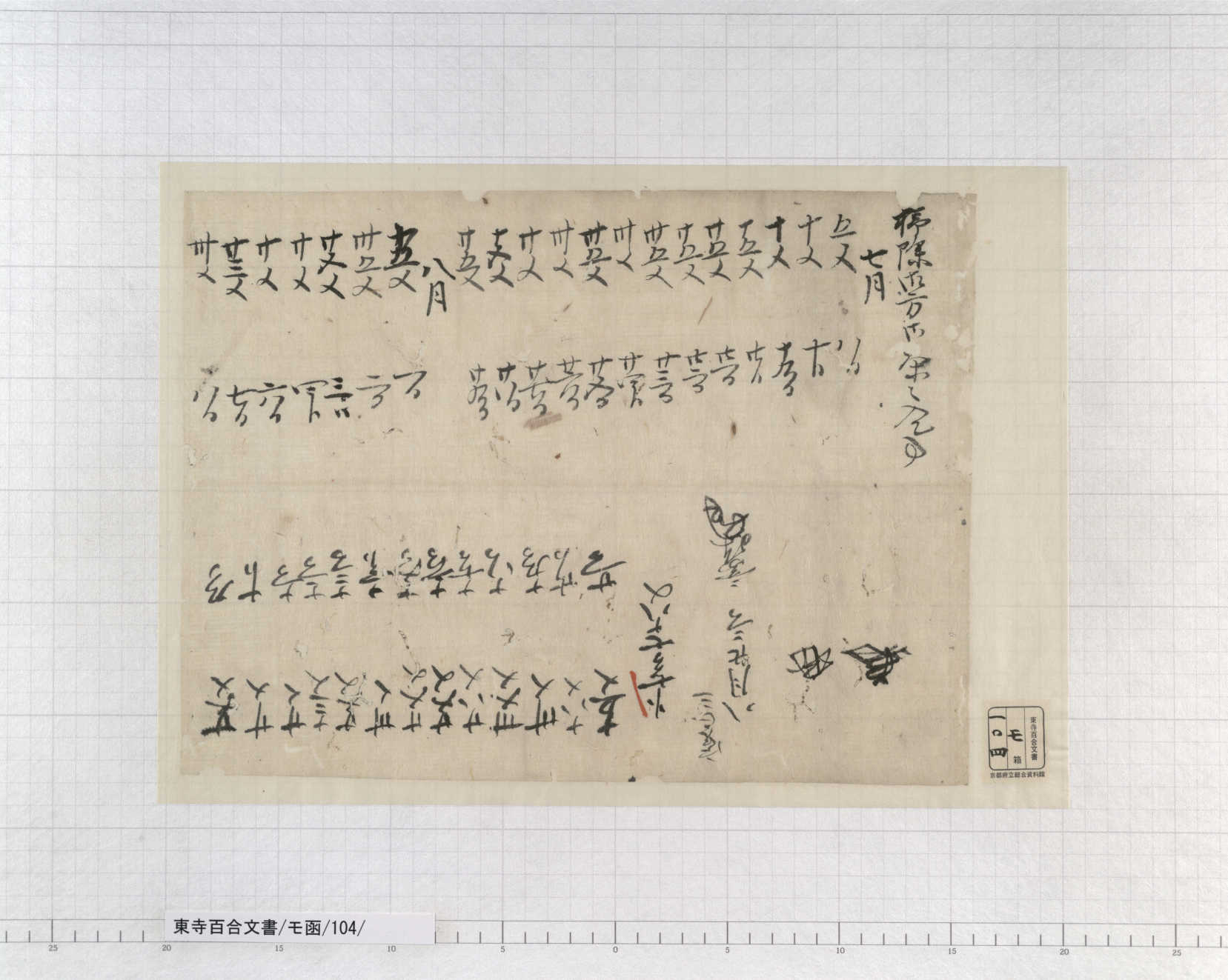

The image above shows six documents, each of which includes one red line.The first four documents specify food and drink served to workers from August 8 to 11.For example, expenses incurred on servings to 18 laborers on August 8 included 170 mon for alcohol, 90 mon for Mochii, and 2 mon for Sandoiri.“Mochii (もちい)” is equivalent to mochi (rice cake) in the present day, made by pounding, rounding and spreading steamed rice. Probably Mochii was served with alcohol as a snack.“Sandoiri (三度入)” refers to alcohol cups. Small expenses were also incurred on alcohol cups every time alcohol was served.Although Sandoiri were made from earth, some may have been broken every time, and new ones had to be purchased. It is possible that people regarded Sandoiri as semi-disposable cups, just like today’s paper cups.

The fifth document is “Onari-kata Soji Kusakari Charyosoku-nokoto”.It shows that the expenses incurred on tea served to 15 laborers who undertook cleaning (“Soji (掃除)”) and mowing (“Kusakari (草刈り)”) on August 11 stood at 75 mon (5 mon per laborer).The Onari by Ashikaga Yoshimasa took place on August 22 (late September in the present calendar).Preparations for the Onari started more than one month before that, when it was still very hot.There is also a document that lists all the tea expenses incurred during the preparations period from July 8 to August 21:

Tea expenses of 5 to 35 mon are recorded every day, without missing any single day.Because no refrigerators existed back in those days, it must have been impossible to serve tea cold in summer. Nevertheless, it seems that tea was indispensable for breaks.

Meals were often served to laborers.In those days, people typically had two meals in a day (breakfast and dinner). The meal equivalent to today’s lunch was called “Kenzui ‘(硯水・間水)” or “Chujiki (中食)”. People definitely needed sufficient meals when they did physically demanding work.Let’s look at some examples.

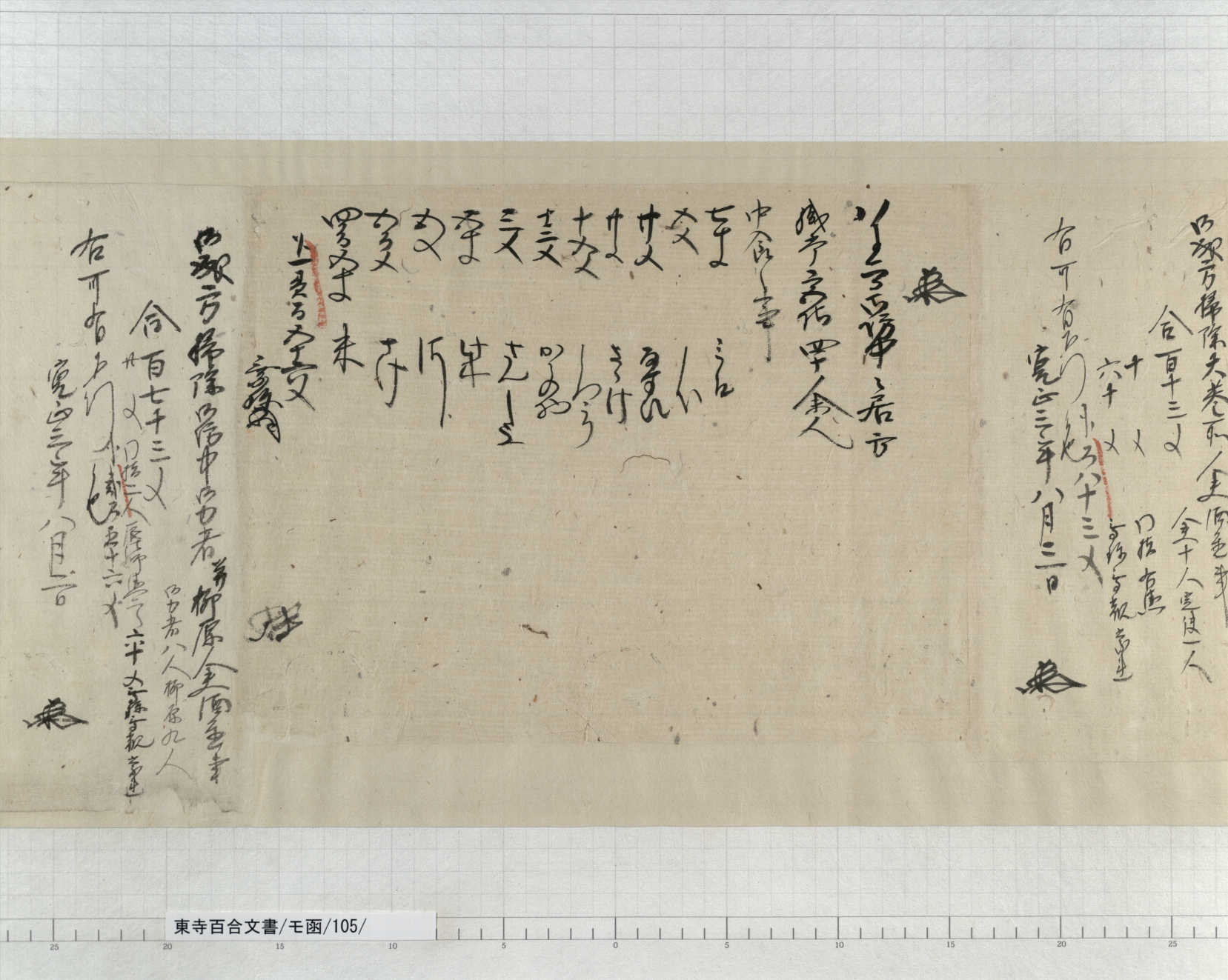

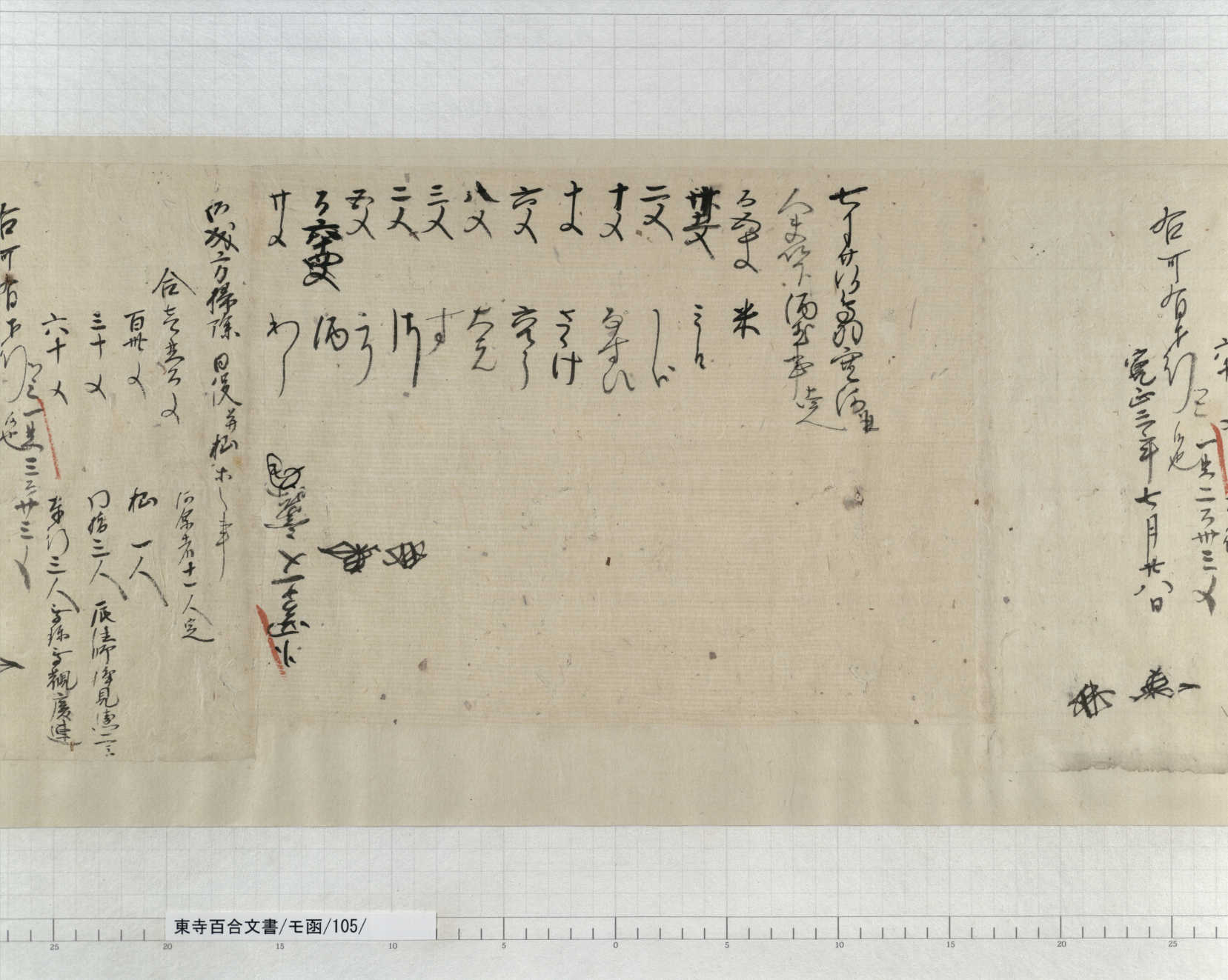

Here, the following items were prepared for Chujiki served to 40 workers:

Miso (soybean paste), Shiho (salt), Nasuhi (eggplant), Sasake (cowpeas), Shirouri (melon cucumber), Kaunomono (pickled vegetables), Sansho (Japanese pepper), Shiba (firewood), Hashi (chopsticks), Sake (alcohol), and Kome (rice); 11 items in total, costing 1 kan 156 mon.

Here, 14 workers were served:

Kome (rice), Miso (soybean paste), Shiho (salt), Nasuhi (eggplant), Sasake (cowpeas), Rokuteu (Rokujo tofu (soybean curd)), Daikon (Japanese white radish), Su (vinegar), Hashi (chopsticks), Uri (gourd), Sake (alcohol), and Wara (straw); 12 items in total, costing 411 mon.

These lists list not only food materials, but also chopsticks and cooking fuels (firewood and straw). It may look peculiar, but you should note that people could not handily switch on gas or electricity in those days. Maybe these documents were more like our barbecue shopping lists, back in the time when cooking started with making a fire.

Eggplant, cowpeas, gourd, tofu, etc. are suitable materials for summer, even though the lists do not specify how they were cooked.Workers must have relished their dishes, which also contained seasoning materials, such as pickled vegetables and Japanese pepper.

★It is difficult to convert the currency in those days into today’s value. In the year of the Onari (1462), the price of 1 kg of rice was approximately 4.8 mon, almost equal to one cup of tea served on the above occasions.