The Hyakugo Archives

Toji Hyakugo Monjo (東寺百合文書) refers to a collection of medieval Japanese documents originally preserved at Toji, a Buddhist temple in Kyoto. The huge collection comprises nearly 25,000 documents spanning roughly 1,000 years, from the 8th to 18th centuries. The bulk of the collection dates from the 14th and 15th centuries.

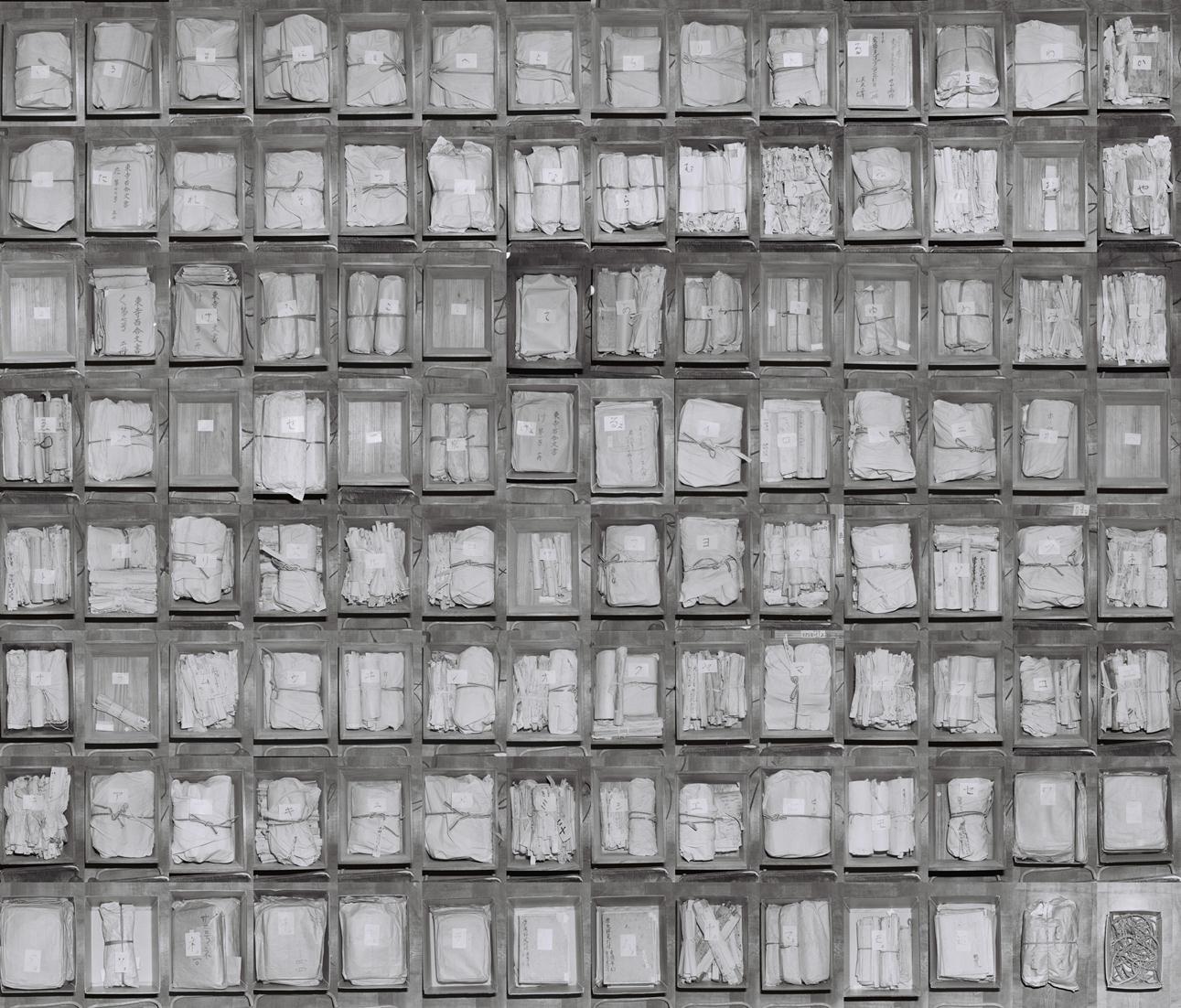

The collection is known as “Toji Hyakugo Monjo (lit. One hundred lidded boxes of documents),” because the documents have been preserved in 100 paulownia document storage boxes donated to Toji during the Edo period by Maeda Tsunanori, lord of the Kaga Domain.

The writings are in kanji characters and kana syllabary, handwritten with brush and India ink on washi (Japanese paper).

Toji Hyakugo Monjo today belongs to Kyoto Prefecture, which purchased it from Toji in 1967. It is housed in a storage facility of the Kyoto Institute, Library and Archives.

Because of its outstanding value as a historical source, the Toji Hyakugo Monjo was designated a national treasure in 1997.

Toji

Kyo-o Gokokuji (教王護国寺) is the official name of Toji, the Buddhist temple that originally housed the Hyakugo Monjo.

Toji was established in 796, almost immediately following the relocation of the capital to Kyoto in 794.

Toji was built by the state for the spiritual protection of the nation. It is located to the east of the former site of the no longer existing Rajomon Gate, which was in effect the main gate into the city. Toji (lit. East Temple) originally had a twin “West Temple,” known as Saiji, flanking the western side of Rajomon Gate. Saiji, however, soon went into decline after having lost most of its buildings to fire and other causes by the end of the 10th century, and no longer exists today. Toji, on the other hand, thrives to this day, having become a major center of the Shingon school of Japanese Buddhism.

In 823, Emperor Saga presented Toji to Kukai (空海), the monk who founded the Shingon school. Kukai had earlier returned from the Chinese continent, where he had studied extensively about Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty. Kukai operated Toji as a konpon dojo (根本道場, central training hall) of Shingon Buddhism, where only Shingon monks were permitted. Kukai was also actively involved in the construction of the temple buildings, which was still ongoing at the time. Posthumously known as Kobo Daishi, Kukai has remained greatly admired in posterity, widely the object of popular worship in the Kamakura period (13th century) and beyond.

Reasons for the Hyakugo Archives Suvival

The superior permanence of washi (和紙) and India ink (墨) has enabled the manuscripts to last for a long period of time. In addition to such material characteristics, the survival of the documents over many different eras is significantly owing to how people have treated them.

In medieval times when the documents were still in use (or “alive”), the monks at Toji maintained the documents under strict control: heads of monastic organizations kept them close at hand, or they were stored in the library or treasure house of Sai-in Mieido (西院御影堂, Kukai’s former living quarters at Toji). Documents kept close at hand by heads of monastic organizations were those necessary for day-to-day clerical work, or for the running of meetings. Examples include copies/duplicates of important documents, such as certificates of rights, and meeting minutes, referred to as hyojo hikitsuke (評定引付). The originals of such important documents that were duplicated by officials and stored in their tefumibakos were stowed in the library of Sai-in Mieido. The library contained a number of document storage boxes from each monastic organization, and the documents inside each box were neatly arranged by category and cataloged. The management of the library was the responsibility of the officials of the Nijuikku-kuso-kata (廿一口供僧方), the foremost monastic organization at Toji. The removal and return of materials from and to the library were strictly controlled: this had to be performed by Mieido’s hijiri (聖) monk, in the presence of two or more other monks. “Sai-in Bunko Suito-cho (西院文庫出納帳),” a record of document retrieval and return that is among the surviving documents of the Hyakugo Monjo, still provides clear details of what documents were retrieved and returned by whom and when. The treasure house contained documents pertaining to state Buddhist services organized and executed by the choja (abbot) of Toji, as well as Heian-period documents concerning temple-owned estates and temple management. Examples include documents associated with Buddhist services, such as Goshichinichi-mishiho and Kechien-kanjo. These documents were under the control of the shigyo (who assisted the choja) of Toji.

As a result of social changes, such as the replacement of the conventional shoen system with systems of landownership more characteristic of early modern times, “medieval documents” of previous eras ceased to be valid for claiming rights and privileges. The documents became obsolete, no longer serving any practical purpose. Such documents became part of the archives, serving purposes different from those they were originally intended for. In the Edo period, both the shogunate (central government) and daimyo (regional lords) promoted learning, actively engaging in the compilation of history books and topographical descriptions. Maeda Tsunanori (前田綱紀), fifth lord of the Kaga Domain, was one such academically inclined daimyo, who dispatched retainers to various parts of the country in pursuit of books. Tsunanori also borrowed manuscripts from Toji, copying and cataloging them. When he finished working with the documents in 1685, Tsunanori donated to Toji 100 paulownia boxes for storing the vast number of documents. Stowed in these paulownia boxes, the archived documents have survived to this day.

The Hyakugo Archives Today

Old Japanese manuscripts written on washi with brush and India ink are generally tolerant of long-term storage, but they do sustain damage from insects and other causes. Toji Hyakugo Monjo is no exception, and some documents with severe damage have undergone restoration. To date, 9,948 documents—about half the documents in the Hyakugo Monjo—have been restored, in ways that take into account their storage and utilization methods, and as a rule retain their original forms. Detailed records of restoration are also maintained. The remaining half, that is, 8,756 documents, are still preserved in their original condition, unaltered since they were written, and folded in exactly the same manner as they were in medieval times. This makes them excellent materials for studying not just the contents of the manuscripts but the manuscripts as objects, including, for example, the study of medieval paper.